Gallup asked students about their levels of support and deep learning during college.

These factors - from feeling supported by a professor to having work experiences that allowed them to apply what they were learning in the real world - more than doubled their odds of engagement and success after school. And yet only 14% of students get all three elements of support and only 6% get all three. (It's nice to see that nearly two-thirds encounter at least one professor who makes them excited about learning and nearly a third are on a project that lasts longer than a semester.) But all of these seems kind of random: just 3% get all six elements during their university education.

3% suggests to me that these results have nothing to do with the educational system and everything to do with enterprising students and professors who are working outside of the system. It's nice that heroic and enterprising students and professors are out there. It would probably be more effective if we actually designed universities to provide these experiences for students, making this sort of mentoring a part of professors' 30 to 50 work week (instead of expecting them to do this outside of their regular teaching and research) and making these sorts of work experiences a normal part of an education.

31 May 2014

30 May 2014

Who Would Have Believed that Obama Would be Worse at Communication than Bush?

About the time the US went from silent movies to talkies, presidents seemingly stopped talking and became images instead of leaders who provided a narrative.

Obama press secretary Jay Carney's retirement is a good opportunity to look at Obama's effort to communicate.

George W. Bush was able to initiate two wars, a department of Homeland Security, TARP, and a massive tax cut. His record of legislative initiatives was not as great as LBJ's list of Great Society initiatives, but at least he matched LBJ for the average number of press conferences per year. It didn't matter that he had a penchant for butchering the language, he put effort into talking directly to the American people.

Obama? Not so much.

Obama's average of 20 press conferences per year puts him below either of the Bush men or Clinton. Congress has made it clear that no issues are as important to them as obstructing any of his initiatives, but Obama hasn't exactly made extraordinary efforts to communicate directly to the American people. In this age of 24-7 news coverage, you might think that he could at least dictate the topic, if not the position on them. (I remember feeling so flabbergasted at George W. Bush's administration's ability to convince the American people that of all the things we could be focused on, Iraq was the one that deserved the most attention. As much as I opposed the war even then, this is pretty great example of what it means to control the narrative, to dictate the topics that receive attention.)

FDR averaged nearly as many press conferences per year as Obama has average per term. And he passed legislation at least the scope of Obamacare about once per year. Can you imagine what FDR would make of the incredible possibilities offered by continuous news coverage?

Just judging from the paucity of press conferences, it doesn't seem as though Obama believes that he can talk over the heads of Congress directly to the American people. I wonder what FDR would say to him about that?

George W. Bush was able to initiate two wars, a department of Homeland Security, TARP, and a massive tax cut. His record of legislative initiatives was not as great as LBJ's list of Great Society initiatives, but at least he matched LBJ for the average number of press conferences per year. It didn't matter that he had a penchant for butchering the language, he put effort into talking directly to the American people.

Obama? Not so much.

Obama's average of 20 press conferences per year puts him below either of the Bush men or Clinton. Congress has made it clear that no issues are as important to them as obstructing any of his initiatives, but Obama hasn't exactly made extraordinary efforts to communicate directly to the American people. In this age of 24-7 news coverage, you might think that he could at least dictate the topic, if not the position on them. (I remember feeling so flabbergasted at George W. Bush's administration's ability to convince the American people that of all the things we could be focused on, Iraq was the one that deserved the most attention. As much as I opposed the war even then, this is pretty great example of what it means to control the narrative, to dictate the topics that receive attention.)

FDR averaged nearly as many press conferences per year as Obama has average per term. And he passed legislation at least the scope of Obamacare about once per year. Can you imagine what FDR would make of the incredible possibilities offered by continuous news coverage?

Just judging from the paucity of press conferences, it doesn't seem as though Obama believes that he can talk over the heads of Congress directly to the American people. I wonder what FDR would say to him about that?

28 May 2014

Why Crowded Cities Provide the Space for Creativity

One reason that women migrate into cities is because they are more free to create their own lifestyle. At the extreme, you can think of the girl raised in a Taliban village who would be free to choose whether to wear a veil or jeans and t-shirt if she moved into the anonymity of a big city in the West. To a lesser extent, even moving from a small rural area where people don't just know you but also know your grandparents will make it easier for a young girl raised Amish, say, to pursue a career and buy a BMW without accusation of being pretentious.

When you socialize with folks you know well -and who know you well - you are less likely to encounter new ideas. Job leads tend to come from folks outside of your immediate circle of friends. More than that, loose acquaintances are people with whom we're free to try on new ideas and new ways of being. Someone from a small town who knows that you get your half grin from your grandpa are less likely to let you become someone new than an acquaintance in a city who barely knows you. This freedom not only lets the Amish girl wear lipstick but it lets the inventor explore new ideas The more varied our interactions, the more potential for novelty.

When you socialize with folks you know well -and who know you well - you are less likely to encounter new ideas. Job leads tend to come from folks outside of your immediate circle of friends. More than that, loose acquaintances are people with whom we're free to try on new ideas and new ways of being. Someone from a small town who knows that you get your half grin from your grandpa are less likely to let you become someone new than an acquaintance in a city who barely knows you. This freedom not only lets the Amish girl wear lipstick but it lets the inventor explore new ideas The more varied our interactions, the more potential for novelty.

Curiously, this freedom leads to innovation, both technological and social. It's not just personal lives that get invented within the anonymity of a city: a handful of cities generate more patents than the rest of the country combined.

20 cities generate 63% of all patents in the US.

The research universities that are within these regions help to provoke a great deal of the innovation. They also tend to cultivate a spirit of openness and tolerance for new ideas and dis-respect for authority that fosters innovation. People in these innovative cities are more likely to be individualistic and are less family oriented than folks in less innovative cities. Innovation isn't something that gets neatly contained to work.

When you socialize with folks you know well -and who know you well - you are less likely to encounter new ideas. Job leads tend to come from folks outside of your immediate circle of friends. More than that, loose acquaintances are people with whom we're free to try on new ideas and new ways of being. Someone from a small town who knows that you get your half grin from your grandpa are less likely to let you become someone new than an acquaintance in a city who barely knows you. This freedom not only lets the Amish girl wear lipstick but it lets the inventor explore new ideas The more varied our interactions, the more potential for novelty.

When you socialize with folks you know well -and who know you well - you are less likely to encounter new ideas. Job leads tend to come from folks outside of your immediate circle of friends. More than that, loose acquaintances are people with whom we're free to try on new ideas and new ways of being. Someone from a small town who knows that you get your half grin from your grandpa are less likely to let you become someone new than an acquaintance in a city who barely knows you. This freedom not only lets the Amish girl wear lipstick but it lets the inventor explore new ideas The more varied our interactions, the more potential for novelty.

I have spent considerable time in 6 of the top 10 cities in the list above. They are characterized by what I'd call personality. Santa Cruz, Boulder, and Austin share a very similar vibe and the folks living there certainly don't match the description conservatives would give of capitalists. These are places that aren't merely tolerant of diversity: they celebrate it. The 6 cities I know lean left - to a considerable degree. They are places that are more likely to support people than judge them, less likely to require drug testing for welfare recipients than to legalize pot. It is in these milieus from which creativity emerges. It's not just that conservatives have very little support among creative types in the arts; conservative cities and rural areas have very little patent activity. When I lived in Santa Cruz in the early 1980s, it was the only city in the US with an openly gay, communist mayor. Austin has a campaign to "Keep Austin Weird." Yesterday I ate in Native Foods in Boulder, a place that more traditional communities might chuckle at for its unabashed embrace of organic, vegan food. It's little wonder that these communities are cradles to new ideas. It is, to me, no coincidence that 3 of the top ten cities in this list are in California's Bay Area, a place where people seemingly feel little compunction about conformity - whether in thought, dress, or lifestyle - a home to the Free Speech Movement that helped to usher in "the 60s."

All cities - and some more than others - provide space for the individual to step outside of tradition. Unsurprisingly, being open to novelty is a package deal: whether you first open the door to social invention or technological invention, the disrespect for tradition is likely to spill into all walks of life.

-------------

Graphs are from a Brookings report here. Claims about how people in different cities poll on topics like family or individualistic tendencies come from p. 143 of Bill Bishop's The Big Sort.

26 May 2014

Superman Reveals the Most Important Super Power

Superman explains to young Timmy that the reason he has changed from using phone booths to using photo booths is because it's now about image, not communication, connection, change ... well, whatever it was about in the days of phone booths.

"It's more important to be photogenic than to change," he tells Timmy. "If you could wish for one super power, photogenic should be it," he continued. "If you don't look good on the movie posters, no one will ever come to the cinema to find out what else you can do."

And then, he tucked the photo booth under his arm, said, "I'm going to need this for selfies!" saluted Timmy, and flew off.

"It's more important to be photogenic than to change," he tells Timmy. "If you could wish for one super power, photogenic should be it," he continued. "If you don't look good on the movie posters, no one will ever come to the cinema to find out what else you can do."

And then, he tucked the photo booth under his arm, said, "I'm going to need this for selfies!" saluted Timmy, and flew off.

24 May 2014

Covey's Lighthouse as a Symbol of Transition Rather Than Permanence

I used to work for Covey Leadership Center. Stephen Covey liked lighthouses. For him they were a symbol of stability. The lighthouse would faithfully stand there warning ships to stay away from the rocks, from danger.

For me, a lighthouse is instead a symbol of transition. It's not that people on boats can't come up to land. In fact, getting onto land is probably the whole purpose of the trip they've made by sea. The lighthouse instead of warning them to stay away signals that it's time for a transition. The lesson is, what has brought you this far won't work for the next stage of your travel. You'll have to get out of your ship and into a train or car or even onto your own two feet. You have options but the ship isn't one of them. You've reached land now and can't expect to float over this next bit.

This is what happens when you leave behind childhood for your teen years, when you leave the single life behind for the married life, become a parent ... well, so many transitions require us to get outside of ourselves and enter into something different, to become someone else.

Lighthouses aren't secrets. It's almost cliche to talk about how a life changes when you become a parent, or a grad student for instance. It's not hard to see a lighthouse. But the message of the lighthouse is not always so clear. Lighthouses don't warn you back to sea. They simply say that a transition is coming and you need to pay closer attention than you have. You even have your choice of new vessels; there are a variety of choices about how to navigate this new surface. You have a variety of choices but the vessel you've been in up until now is not one of them. Who you've been is no longer an option.

For me, a lighthouse is instead a symbol of transition. It's not that people on boats can't come up to land. In fact, getting onto land is probably the whole purpose of the trip they've made by sea. The lighthouse instead of warning them to stay away signals that it's time for a transition. The lesson is, what has brought you this far won't work for the next stage of your travel. You'll have to get out of your ship and into a train or car or even onto your own two feet. You have options but the ship isn't one of them. You've reached land now and can't expect to float over this next bit.

This is what happens when you leave behind childhood for your teen years, when you leave the single life behind for the married life, become a parent ... well, so many transitions require us to get outside of ourselves and enter into something different, to become someone else.

Lighthouses aren't secrets. It's almost cliche to talk about how a life changes when you become a parent, or a grad student for instance. It's not hard to see a lighthouse. But the message of the lighthouse is not always so clear. Lighthouses don't warn you back to sea. They simply say that a transition is coming and you need to pay closer attention than you have. You even have your choice of new vessels; there are a variety of choices about how to navigate this new surface. You have a variety of choices but the vessel you've been in up until now is not one of them. Who you've been is no longer an option.

Financial Markets and a New Definition of Taking a Bath

Global financial assets are well over $200 trillion, doubling every decade since 1990. In 1990, total debt and equity outstanding was $50-some trillion. By 2000 it was over $100 trillion. By 2010, it was over $200 trillion.

Between 1995 and 2007, only one quarter of this additional financing went to corporations and households. This money is not being used to start or expand businesses or even to finance purchases by households of everything from refrigerators to university educations.

Every decade we double our financial assets but of late those assets are merely going into speculative sorts of enterprises as opposed to financing actual economic activity.

The result is something akin to water in a bathtub, waves sloshing about in a closed system. Financing is used to finance financial activity and it rushes in and then out, creating odd turbulence without actually flowing into anything new.

The problem is not the volume of financing. That's actually a wonderful thing. The problem is that our limit no longer lies in the quantity of financing; that financing is limited by where it can go. We still haven't created enough viable opportunities for that financing, from public to private sector ventures. Until we do, we'll keep trying to predict the movement of waves in a tub.

Between 1995 and 2007, only one quarter of this additional financing went to corporations and households. This money is not being used to start or expand businesses or even to finance purchases by households of everything from refrigerators to university educations.

Every decade we double our financial assets but of late those assets are merely going into speculative sorts of enterprises as opposed to financing actual economic activity.

The result is something akin to water in a bathtub, waves sloshing about in a closed system. Financing is used to finance financial activity and it rushes in and then out, creating odd turbulence without actually flowing into anything new.

The problem is not the volume of financing. That's actually a wonderful thing. The problem is that our limit no longer lies in the quantity of financing; that financing is limited by where it can go. We still haven't created enough viable opportunities for that financing, from public to private sector ventures. Until we do, we'll keep trying to predict the movement of waves in a tub.

21 May 2014

Is the Web Conscious?

Systems have characteristics that their parts do not. This emergent phenomenon defines them. Your car got you to work today. None of its parts could do that. Not the engine. Not the wheels. Not the drive train. Systems are defined by the interactions of their parts rather than the action of their parts.

Which brings me to global consciousness.

James Surowiecki, author of The Wisdom of Crowds, wrote an interesting piece in the New Yorker titled "The Collective Intelligence of the Web." The first example he uses of collective intelligence is of a project NASA began in 2000 to map Mars.

He goes on to write about how Google ranks pages based on the actions of millions of users, and cites other examples. This isn't just about judgment. This is about creating. At one level this is not new. For centuries humans have been walking down trails that have been defined by the steps of thousands of people who have come before. But this capability of the Internet to knit together individual consciousness into something collective is something newly emergent, it seems to me.

Collectively, civilization can do what individuals can't. On our own, we really are just intelligent apes. But with one other person we can create a new human. With one million other people we can create a new community or set of institutions. And with billions of people online, maybe we can create a new sort of understanding that would be impossible for the individual or even any community within it.

It might just be that the web is enabling a new kind of consciousness to emerge, awareness and problem solving and project execution that would never be possible at the level of individuals or even teams traditionally managed. If so, it raises a fascinating question. Has the web developed consciousness yet? And if it was self-aware, would we be aware of it?

Which brings me to global consciousness.

James Surowiecki, author of The Wisdom of Crowds, wrote an interesting piece in the New Yorker titled "The Collective Intelligence of the Web." The first example he uses of collective intelligence is of a project NASA began in 2000 to map Mars.

"There were two very interesting things about the results. First, although there was no financial incentive to participate, more than a hundred thousand people took part in the study, generating more than 2.4 million clicks. Second, and even more striking, the collective product of all those amateur clickers was very good—as a report put it, their 'automatically computed consensus” was “virtually indistinguishable from the inputs of a geologist with years of experience in identifying Mars craters.'"

He goes on to write about how Google ranks pages based on the actions of millions of users, and cites other examples. This isn't just about judgment. This is about creating. At one level this is not new. For centuries humans have been walking down trails that have been defined by the steps of thousands of people who have come before. But this capability of the Internet to knit together individual consciousness into something collective is something newly emergent, it seems to me.

Collectively, civilization can do what individuals can't. On our own, we really are just intelligent apes. But with one other person we can create a new human. With one million other people we can create a new community or set of institutions. And with billions of people online, maybe we can create a new sort of understanding that would be impossible for the individual or even any community within it.

It might just be that the web is enabling a new kind of consciousness to emerge, awareness and problem solving and project execution that would never be possible at the level of individuals or even teams traditionally managed. If so, it raises a fascinating question. Has the web developed consciousness yet? And if it was self-aware, would we be aware of it?

Happiness like a Heartbeat

Gallup tracks happiness in the US. It doesn't seem to be moving in any particular direction but there is a lot of movement. To me it looks like a heartbeat. For some reason that seems fitting and makes me happy.

20 May 2014

Why The Rapid Recovery in Startups Might Not Be Enough

The good news is that the number of

startups is rebounding to where it was in the late 1990s. The bad news is that

because of economic changes, it takes more startups than ever to employ the

same number of people.

There has been a sharp uptick in the number of startups in just the last few years. (The bureau of labor statistics has reported numbers only through March of 2013.)

In 2013, the

number of companies less than 2 years old rose by 14%.

The problem is not just that it is

taking the rate of business formation a few years to return to normal. The

problem is that startups don't create as many jobs.

Software is now automating knowledge

work just as machines have been – for centuries – automating physical work.

While this raises productivity it destroys jobs.

It’s cliché – but still true – to

say that the pace of innovation is obsoleting products, companies and jobs more

rapidly than ever. As companies rapidly expand, shrink, and shift focus, they

more rapidly create and destroy jobs.

Outsourcing is more common and

that’s one reason that even successful entrepreneurs don’t need as many

employees. The Kauffman Foundation reported that startups that needed about 8

employees in 2000 could support the same level of sales with only 5 employees

today.

Automation, innovation, outsourcing

and greater efficiencies contribute to an incredibly dynamic job market. In the

second quarter of 2013, the US economy created 7.1 million jobs and destroyed

6.5 million. The net result was 603,000 more jobs than we had at the beginning

of the quarter. That’s nice. But given the rate at which jobs are being

destroyed, the economy has to create 12 new jobs in order to gain one. Compared

to the number of entrepreneurs we’d need in a fictional world where jobs are

created and kept for the length of a career, in this world we need about 12

times as many entrepreneurs.

The good news is that the rate of

startups is recovering. The bad news is that it needs to be higher than it has ever

been before in order to create enough jobs to bring back wage growth and full

employment.

The Politics of Location

Politically, counties are becoming more sharply divided. Between 1976 and 2008, the percentage of counties where the Republican or Democratic presidential candidate won by 20 points or more doubled from roughly 25% to nearly 50%. Increasingly, we vote like our neighbors.

Curiously, this tendency doesn't just define us as conservative or liberal. It's finer tuned than that. In the primary election between Obama and Hillary Clinton - two senators with nearly identical voting records - half the voters lived in counties where Obama or Clinton won by landslides. We side with our neighbors on differences large or small.

It seems that politics is like fashion, food and accents: it has a distinctly regional flavor.

Facts above come from Bill Bishop's interesting book The Big Sort, Why the Clustering of Like-Minded Americans is Tearing us Apart.

Curiously, this tendency doesn't just define us as conservative or liberal. It's finer tuned than that. In the primary election between Obama and Hillary Clinton - two senators with nearly identical voting records - half the voters lived in counties where Obama or Clinton won by landslides. We side with our neighbors on differences large or small.

It seems that politics is like fashion, food and accents: it has a distinctly regional flavor.

Facts above come from Bill Bishop's interesting book The Big Sort, Why the Clustering of Like-Minded Americans is Tearing us Apart.

16 May 2014

Republican Fondness for Conspiracy Theories

The folks at Public Policy Polling asked Americans about conspiracy theories. As it turns out we like them. And curiously, folks who voted for Romney are more likely to believe in a good conspiracy theory than are the folks who voted for Obama.

Here's a table showing the ratio of Romney to Obama supporters who believe in a particular conspiracy.

Voters come together on a belief in aliens and the government adding fluoride for sinister reasons.

They are sharply divided over whether global warming is a hoax and whether Bush misled on weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. (Note that the question is not whether the science on global warming is dubious or incomplete: 61% of Romney supporters actually think global warming is a hoax that scientists are perpetuating at the expense of innocent oil companies, politicians, and talk radio personalities.) That seems predictable given politics.

It's less clear why Romney supporters would be about twice as likely to believe that a UFO crashed at Roswell or in lizard people.

The fact that Republicans are more likely to cozy up to a good conspiracy doesn't prove that the GOP platform is carefully crafted to appeal to the interests of average Americans while helping only a select few. Then again, if you could prove such a claim it wouldn't be much of a conspiracy, would it?

Here's a table showing the ratio of Romney to Obama supporters who believe in a particular conspiracy.

| Voted For | |||

| Conspiracy | Obama | Romney | Ratio |

| Believe Global Warming a Hoax? | 12 | 61 | 5.1 |

| Believe Obama is Anti-Christ | 5 | 22 | 4.4 |

| Believe in lizard people | 2 | 5 | 2.5 |

| Believe in New World Order | 16 | 38 | 2.4 |

| Believe Sadam was involved in 9/11 | 19 | 36 | 1.9 |

| Believe UFO Crashed at Roswell? | 16 | 27 | 1.7 |

| Believe govt spreads chemicals thru plane exhaust | 3 | 5 | 1.7 |

| Believe pharma and med invent new diseases to make $ | 11 | 17 | 1.5 |

| Believe govt controls minds thru TV | 12 | 18 | 1.5 |

| Believe in Bigfoot | 12 | 15 | 1.3 |

| Believe McCartney died and was replaced | 4 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Believe Vaccines Cause Autism | 19 | 22 | 1.2 |

| Believe in JFK conspiracy | 47 | 54 | 1.1 |

| Believe aliens exist | 28 | 28 | 1.0 |

| Believe govt adds fluoride for sinister reasons | 8 | 8 | 1.0 |

| Believe Moon Landing was Fake | 6 | 5 | 0.8 |

| Believe govt allowed 9/11 to happen | 13 | 8 | 0.6 |

| Believe CIA spread crack in inner cities | 17 | 10 | 0.6 |

| Believe Bush misled on WMDs in Iraq | 69 | 18 | 0.3 |

Voters come together on a belief in aliens and the government adding fluoride for sinister reasons.

They are sharply divided over whether global warming is a hoax and whether Bush misled on weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. (Note that the question is not whether the science on global warming is dubious or incomplete: 61% of Romney supporters actually think global warming is a hoax that scientists are perpetuating at the expense of innocent oil companies, politicians, and talk radio personalities.) That seems predictable given politics.

It's less clear why Romney supporters would be about twice as likely to believe that a UFO crashed at Roswell or in lizard people.

The fact that Republicans are more likely to cozy up to a good conspiracy doesn't prove that the GOP platform is carefully crafted to appeal to the interests of average Americans while helping only a select few. Then again, if you could prove such a claim it wouldn't be much of a conspiracy, would it?

11 May 2014

How Catholic Confession Has Created Sex Scandals and Driven Members Out of the Church

Before looking at the following graph, keep in mind that the Catholic Church has been around about 1,700 years. Had the church lost just 6 percentage points of its believers each of the last 17 centuries, it would now be effectively obsolete, making Catholics about as common as pagans. Again, losing 6 percentage points per century would have obsoleted it by now.

Which brings us to the precipitous decline of Hispanics who refer to themselves as Catholic in the US.

In just four years, the church has lost 12 percentage points. At this rate, within 25 years no Hispanics will be Catholic. In terms of the time the Church has been around, a quarter of a century is a rounding error.

It's a safe bet that the church won't dissipate that quickly, but it's worth asking how Pope Francis could slow this decline.

I have two complementary theories, one having to do with confession and the other with the modern emphasis on autonomy - the self-defined life that is at the root of democracy and capitalism.

Sex scandals have hurt the church. That seems obvious. Less obvious is the persistent role of confession in sex scandals.

Centuries ago,a young woman confessing to immoral urges was positioned on her knees before the priest, her arms on his legs in a penitent position. Even the most sincere young priest, looking into the face of a beautiful confessor gazing up at him, her face essentially on his lap, would find it hard not to be moved as she confessed to sinful thoughts or acts. So a long time ago, the church decided that a confession booth would both take some of the sexual tension out of this situation and possibly protect the identity of easy marks from rogue priests. Things got better.

Then, in 1910, Pope Pius X decided that children should confess. He thought it was a good idea for 7 year old kids to begin admitting they were sinners. (The list of serious sins includes being late for Mass. It's never too early for someone to start feeling guilty, apparently, even for things for which parents are responsible.) And while the previous practice was to confess once or twice a year, Pius thought confession should become a weekly practice. So about the time everyone else began to listen to weekly radio programs, priests were listening to weekly confessions from prepubescent children.

After this policy, reports of sexual abuse of children rose. It's a terrible policy.

One difference between a church and business is the respect for tradition. It takes a lot to change the policy of a previous pope because that pope was the mouthpiece of God. Even so, popes do change policies. It happens and if Pope Francis cares at all about halting the decline of Catholics, he'll reverse this decision to have children confess. Let children be children and wait until they are teenagers, at least, before beginning to make them feel guilty for living in a body instead of existing as a purely spiritual being, unencumbered by carnal thoughts. That's one policy change that could help to reverse the decline of Catholics.

The second policy change will be harder because it gets at the heart of the difference between Catholics and Protestants.

Authority seems to evolve through at least two stages. In the first stage of nation-states, for instance, the monarch was the ultimate authority. Louis XIV, who ruled France until 1715, famously said, "I am the state." That same century, Thomas Jefferson penned the words, "All men are created equal," and then helped to create a constitution that would replace the monarch as the ultimate authority in a country. At the first stage, authority resides in a person and in a later stage it resides in the written word.

Catholics and Protestants alike believe the Bible is the inspired word of God. The difference is, Protestants think the Bible is the ultimate authority whereas Catholics think the ultimate authority is the clergy (and their ultimate authority is the pope). Catholics warned original Protestants that if they were going to make the Bible the ultimate authority then anyone was free to offer a new interpretation and the result would be thousands of denominations; it turns out they were right. But even in the midst of the chaos of multiple theologies, there is a certain freedom and democracy in the Protestant option. It is not just, as Martin Luther said, "We are all priests." Any Protestant, from Mary Baker Eddy to Billy Graham, is free to be pope, to head his or her own religion. And the Protestant emphasis more closely accords with the impulse of the modern world, with each person defining his or her own life rather than turning to an authority figure for instructions.

Here, too, Pope Francis has a chance to articulate relevant policy. A pope who says, "Who am I to judge," is one that people defining their own life are more likely to love than resent. It would be huge - but honest - for the Catholic Church to acknowledge their role of merely informing rather than defining the individual's conscience. There is a very real difference between a church that helps the individual to define his or her own life and one that wants to define that life.

Hispanics make up nearly half of American Catholics. Their loss is not trivial. It would be absurd for Pope Francis to ignore this problem. The good news for him, though, is that this decline could probably be slowed with just a couple of key changes. It's too late to avoid radical change; the Church is going to either radically change in terms of its numbers or in terms of its policy. We will see whether Francis has more commitment to tradition or reality and which kind of radical change he'll accept. It's too late for the status quo.

Which brings us to the precipitous decline of Hispanics who refer to themselves as Catholic in the US.

In just four years, the church has lost 12 percentage points. At this rate, within 25 years no Hispanics will be Catholic. In terms of the time the Church has been around, a quarter of a century is a rounding error.

It's a safe bet that the church won't dissipate that quickly, but it's worth asking how Pope Francis could slow this decline.

I have two complementary theories, one having to do with confession and the other with the modern emphasis on autonomy - the self-defined life that is at the root of democracy and capitalism.

Sex scandals have hurt the church. That seems obvious. Less obvious is the persistent role of confession in sex scandals.

Centuries ago,a young woman confessing to immoral urges was positioned on her knees before the priest, her arms on his legs in a penitent position. Even the most sincere young priest, looking into the face of a beautiful confessor gazing up at him, her face essentially on his lap, would find it hard not to be moved as she confessed to sinful thoughts or acts. So a long time ago, the church decided that a confession booth would both take some of the sexual tension out of this situation and possibly protect the identity of easy marks from rogue priests. Things got better.

Then, in 1910, Pope Pius X decided that children should confess. He thought it was a good idea for 7 year old kids to begin admitting they were sinners. (The list of serious sins includes being late for Mass. It's never too early for someone to start feeling guilty, apparently, even for things for which parents are responsible.) And while the previous practice was to confess once or twice a year, Pius thought confession should become a weekly practice. So about the time everyone else began to listen to weekly radio programs, priests were listening to weekly confessions from prepubescent children.

After this policy, reports of sexual abuse of children rose. It's a terrible policy.

One difference between a church and business is the respect for tradition. It takes a lot to change the policy of a previous pope because that pope was the mouthpiece of God. Even so, popes do change policies. It happens and if Pope Francis cares at all about halting the decline of Catholics, he'll reverse this decision to have children confess. Let children be children and wait until they are teenagers, at least, before beginning to make them feel guilty for living in a body instead of existing as a purely spiritual being, unencumbered by carnal thoughts. That's one policy change that could help to reverse the decline of Catholics.

The second policy change will be harder because it gets at the heart of the difference between Catholics and Protestants.

Authority seems to evolve through at least two stages. In the first stage of nation-states, for instance, the monarch was the ultimate authority. Louis XIV, who ruled France until 1715, famously said, "I am the state." That same century, Thomas Jefferson penned the words, "All men are created equal," and then helped to create a constitution that would replace the monarch as the ultimate authority in a country. At the first stage, authority resides in a person and in a later stage it resides in the written word.

Catholics and Protestants alike believe the Bible is the inspired word of God. The difference is, Protestants think the Bible is the ultimate authority whereas Catholics think the ultimate authority is the clergy (and their ultimate authority is the pope). Catholics warned original Protestants that if they were going to make the Bible the ultimate authority then anyone was free to offer a new interpretation and the result would be thousands of denominations; it turns out they were right. But even in the midst of the chaos of multiple theologies, there is a certain freedom and democracy in the Protestant option. It is not just, as Martin Luther said, "We are all priests." Any Protestant, from Mary Baker Eddy to Billy Graham, is free to be pope, to head his or her own religion. And the Protestant emphasis more closely accords with the impulse of the modern world, with each person defining his or her own life rather than turning to an authority figure for instructions.

Here, too, Pope Francis has a chance to articulate relevant policy. A pope who says, "Who am I to judge," is one that people defining their own life are more likely to love than resent. It would be huge - but honest - for the Catholic Church to acknowledge their role of merely informing rather than defining the individual's conscience. There is a very real difference between a church that helps the individual to define his or her own life and one that wants to define that life.

Hispanics make up nearly half of American Catholics. Their loss is not trivial. It would be absurd for Pope Francis to ignore this problem. The good news for him, though, is that this decline could probably be slowed with just a couple of key changes. It's too late to avoid radical change; the Church is going to either radically change in terms of its numbers or in terms of its policy. We will see whether Francis has more commitment to tradition or reality and which kind of radical change he'll accept. It's too late for the status quo.

09 May 2014

Why The Country Isn't Ready for President Elizabeth Warren (And Why Culture Matters More Than Policy)

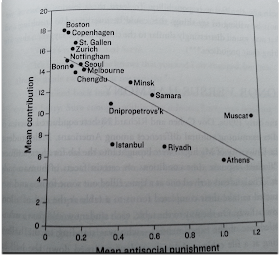

There's a fascinating study on cooperation that has been done around the world. I think it reveals why Elizabeth Warren - a policy maker I love - is not ready to be president. Or, more to the point, why the country is not ready for her to be president.

The study measures cooperation and a sense of the common good. Bostonians demonstrate the highest ranking. Here's how the study (the game?) works.

You and 3 partners start out with $20 each. You can choose to put all, some, or none of your $20 into a central pile. Whatever you put in gets doubled and split between the four of you. So, here are a couple of scenarios.

Everybody Wins:

You start with $20.

You put in $20, they each put in $20, and this $80 gets doubled to $160, which you then split.

You end with $40. (So do they.)

The group gains $80.

You Win:

You start with $20.

You put in nothing, they each put in $20, and this $60 gets doubled to $120, which you then split.

You end up with $50. (They get just $30.)

The group gains $60.

Some Win:

You start with $20.

You put in nothing, two other people put in nothing, and one dupe puts in $20, which gets doubled to $40, which you all split.

You end up with $30. (The dupe gets just $10.)

The group gains $20.

Nobody Wins:

You start with $20.

You put in nothing, the same as everyone else. Your nothing is doubled.

You end up with $20. (So does everyone else.)

The group gains $0.

Now curiously, this game has been played in cities around the world. In some cities, people cooperate to create more wealth. In other cities they don't. The culture changes from place to place.

In Boston, the average contribution per round is close to $20. Massachusetts is one of the richest states (3rd as measured by per capita income) and as befits a region dependent on a highly developed market economy and a mix of public and private sector initiatives, people have developed high degrees of interdependence and trust. Copenhagen is close to Boston on this ranking.

On the other end of the spectrum is Athens. In Greece you're the dupe to put your money into the pot and the culture there suggests that people are trying to avoid becoming the dupe. The average contribution per round in Athens is closer to $6, meaning that game participants create about a third of the wealth. (It seems little wonder that Greece has such trouble with public financing and tax collection.)

The good people of Boston demonstrate the highest levels of cooperation and trust in creating a common good of any city studied. And without that sort of culture, two things are difficult to create: economic progress and, more broadly, a progressive agenda. It's not clear that Elizabeth's policies would seem credible outside of certain areas like Boston, California's Bay Area, Austin, North Carolina's Research Triangle ... essentially places with highly educated work forces working in technologies and industries where cooperation is key. It's one thing to articulate policies that create a common good; it's more difficult to know how to create a culture supportive of such policies. It's easier to know what policy initiatives would help the folks in Boston than it is to know how to change Athen's culture.

There is nothing absolute about the efficacy of policy. Whether particular policy works "depends." A policy rarely works in any condition or culture. Curiously, culture change gets talked to quite a lot within corporations but rarely within nations or neighborhoods. Maybe it's time we changed that.

The study measures cooperation and a sense of the common good. Bostonians demonstrate the highest ranking. Here's how the study (the game?) works.

You and 3 partners start out with $20 each. You can choose to put all, some, or none of your $20 into a central pile. Whatever you put in gets doubled and split between the four of you. So, here are a couple of scenarios.

Everybody Wins:

You start with $20.

You put in $20, they each put in $20, and this $80 gets doubled to $160, which you then split.

You end with $40. (So do they.)

The group gains $80.

You Win:

You start with $20.

You put in nothing, they each put in $20, and this $60 gets doubled to $120, which you then split.

You end up with $50. (They get just $30.)

The group gains $60.

Some Win:

You start with $20.

You put in nothing, two other people put in nothing, and one dupe puts in $20, which gets doubled to $40, which you all split.

You end up with $30. (The dupe gets just $10.)

The group gains $20.

Nobody Wins:

You start with $20.

You put in nothing, the same as everyone else. Your nothing is doubled.

You end up with $20. (So does everyone else.)

The group gains $0.

Now curiously, this game has been played in cities around the world. In some cities, people cooperate to create more wealth. In other cities they don't. The culture changes from place to place.

In Boston, the average contribution per round is close to $20. Massachusetts is one of the richest states (3rd as measured by per capita income) and as befits a region dependent on a highly developed market economy and a mix of public and private sector initiatives, people have developed high degrees of interdependence and trust. Copenhagen is close to Boston on this ranking.

On the other end of the spectrum is Athens. In Greece you're the dupe to put your money into the pot and the culture there suggests that people are trying to avoid becoming the dupe. The average contribution per round in Athens is closer to $6, meaning that game participants create about a third of the wealth. (It seems little wonder that Greece has such trouble with public financing and tax collection.)

The good people of Boston demonstrate the highest levels of cooperation and trust in creating a common good of any city studied. And without that sort of culture, two things are difficult to create: economic progress and, more broadly, a progressive agenda. It's not clear that Elizabeth's policies would seem credible outside of certain areas like Boston, California's Bay Area, Austin, North Carolina's Research Triangle ... essentially places with highly educated work forces working in technologies and industries where cooperation is key. It's one thing to articulate policies that create a common good; it's more difficult to know how to create a culture supportive of such policies. It's easier to know what policy initiatives would help the folks in Boston than it is to know how to change Athen's culture.

There is nothing absolute about the efficacy of policy. Whether particular policy works "depends." A policy rarely works in any condition or culture. Curiously, culture change gets talked to quite a lot within corporations but rarely within nations or neighborhoods. Maybe it's time we changed that.

06 May 2014

The Price of Loyalty to the Tribe

Imagine generations ago, a member of a tribe realized that praying to the god of irrigation didn't make any difference but actually digging trenches from the nearby river did. He even worked out when the trenches should be dug and when they should be closed off, who would do the work, and how much this predictable irrigation would increase crop yields. This benefit would of course make the tribe healthier, support more children so the tribe became larger, and make this irrigation pioneer one of the great men in the tribe.

But of course his great insight was just as likely - perhaps more likely - to have left him alone on the plains, ostracized from the tribe for questioning the beliefs that held the tribe together.

Innovations might make life better but being in the tribe makes life possible.

It's kind of a miracle that anyone has the courage to speak out. Because being right is a consolation prize when you're standing out on the plains, facing the lion alone.

But of course his great insight was just as likely - perhaps more likely - to have left him alone on the plains, ostracized from the tribe for questioning the beliefs that held the tribe together.

Innovations might make life better but being in the tribe makes life possible.

It's kind of a miracle that anyone has the courage to speak out. Because being right is a consolation prize when you're standing out on the plains, facing the lion alone.

02 May 2014

The Dow Set a New All-Time High Yesterday And That's No Big Deal

Imagine that you put $1,000 into a savings account that paid 1% a month. (An obviously fictional example.)

At the end of month one, you'd have $1,010. At the end of month two you'd have $1,020 and some change. By the end of the year, you'd have $1.126.83.

Every month, your savings account would set a new record. It would hit a new, all-time high every single month. That's what happens with a steady rate of return.

Which brings us to the market. For the first time this year, the Dow has hit a new all-time high. Analysts are making noise about whether this means the market has topped out, wondering where else to go with their money.

Whether or not the market is poised for a sell-off has little to do with whether or not it is at an all-time high. In a world with less volatility and no business cycle, the market would be hitting an all-time high every month. Just like your savings account. This is what investments do.

Today's April Jobs Report Adds to the Promise of 2014

This is the jobs report I prematurely forecast last month for March. It took a month longer to happen than I thought, but this ~300,000 jobs report is good news.

288,000 jobs created in April plus the numbers for February and March revised upwards by 36,000 means that a total of 324,000 new jobs were announced this month. We may actually have a year in which monthly job creation numbers average more than 200,000; if so, it will be only the second time since 1999.

The unemployment rate, after being stuck at the same rate for four months, sharply fell. The unemployment rate for April in the last five years leaves little doubt that we're experiencing a real recovery. And it actually seems to be accelerating, 4+ years in.

288,000 jobs created in April plus the numbers for February and March revised upwards by 36,000 means that a total of 324,000 new jobs were announced this month. We may actually have a year in which monthly job creation numbers average more than 200,000; if so, it will be only the second time since 1999.

The unemployment rate, after being stuck at the same rate for four months, sharply fell. The unemployment rate for April in the last five years leaves little doubt that we're experiencing a real recovery. And it actually seems to be accelerating, 4+ years in.

01 May 2014

Spending is Up But Debt is Down. This Might Be the Start of a Sustainable Boom

Last month consumer spending rose 0.9%, its largest uptick since April of 2009. That alone is good news. Even better, families are in a much better position to be spending now.

In April 2009, the economy was beginning to hemorrhage jobs and households were spending between 12 to 13% of their disposable income just to service debt (including mortgage and consumer debt). Just 4 quarters before, household spending on debt had peaked and it was only gradually coming down. Consumer spending was high, which was nice. But it was financed with a lot of debt, which wasn't sustainable.

The Federal Reserve reports the percentage of disposable income that households are spending to service debt here. Their numbers go back to 1980. As you can see, there has been a sharp and steady decline since 2007, just before the crash.

In April 2009, the economy was beginning to hemorrhage jobs and households were spending between 12 to 13% of their disposable income just to service debt (including mortgage and consumer debt). Just 4 quarters before, household spending on debt had peaked and it was only gradually coming down. Consumer spending was high, which was nice. But it was financed with a lot of debt, which wasn't sustainable.

The Federal Reserve reports the percentage of disposable income that households are spending to service debt here. Their numbers go back to 1980. As you can see, there has been a sharp and steady decline since 2007, just before the crash.

At its peak, households were taking on mortgage and consumer debt that their incomes couldn't justify. It's been hard on the economy as households paid down that debt - and as banks refused to offer credit so liberally - but the result is a much more stable position from which to launch a recovery. The bad news is that making this adjustment has been yet another drag on the economy since 2007. The good news is that now we're in a better place.

It's notable that in spite of households rapidly paying down debt and governments at every level shedding jobs, the economy has continued to create jobs during the last four years. Imagine that over the next four years households stop paying down debt and start spending again. Or even optimistically begin to take on more debt. That could be a huge boost to the economy. Consumption is 70% of GDP. Whether households are acting cautiously or spending optimistically makes a huge difference in economic growth.

There are have been a lot of mixed signals in the economy of late. Most notably, this week's report that GDP had grown only 0.1% was particularly disappointing. The economy has made a few false starts during its slow rise during the last four years, has posted a few quarters that suggest the possibility of a boom. It's hard to predict when it might actually take off but one thing is true: the conditions for combustion are the best they've been in nearly twenty years.

Households are spending again but at much lower levels of debt. This could be the start of something sustainable.