- Allen Warren

The folks at etrade sent me a note that starts out:

Not surprisingly, the long and painful bear market has pushed a lot of money to the sidelines. At the end of 2008, cash in money markets and bank accounts had reached nearly $9 trillion or 74% of the value of all publicly traded stocks in the U.S.!

That was the highest such ratio since 1990 — and it would only take a portion of that money moving back into the market to have a powerful effect on stock prices

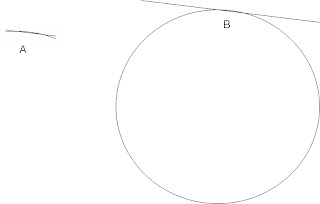

One of the things that I find so fascinating about social reality is how it differs from physical reality. It does not matter whether you suddenly think that a bowling ball is as soft as a marsh mellow - if you drop it on your foot you will feel intense pain. By contrast, if you suddenly think that that stocks are a bad investment, you'll get evidence of just this thing.

There are real and legitimate reasons for markets going up and down. Having said that, there is a great deal of "me too" money that chases after the trends of these dynamics, the money that makes the bubbles and the bubbles pop.

Right now, there is about $9 trillion waiting for stocks to become safe again as an investment. When will stocks again be a safe investment? When that $9 trillion stops waiting.

What do you think is true about financial markets? The real answer is, Whatever you think is true about (or in regards to) financial markets. Of course, as arbitrary as this seems, it can't just be manipulated at will. It's worth remembering that the publishing industry phenomena the year before the financial crash was The Secret.

How could anyone not find cultures, societies, and markets fascinating?