"From Harrisburg to Philadelphia there was a railroad, the first I had ever seen ... In travelling by the road from Harrisburg, I thought the perfection of rapid transit had been reached. We traveled at least eighteen miles an hour, when at full speed, and made the whole distance averaging probably as much as twelve miles an hour. This seemed like annihilating space."

- Ulysses S. Grant, in 1839 as a teenager heading to West Point

31 May 2019

27 May 2019

Predicting the 2020 Election: How the Popular Vote is Driven by the Ratio of Knowledge Workers to Factory Workers

In 1972, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) set quotas for women, minorities and students. Curiously, the party that had championed labor since before FDR, did not set quotas for representation from blue-collar or factory workers. To a degree, they turned their back on this group that Democrats had so surely represented for so many decades.

Instead of focusing on blue-collar workers, they shifted their attention to white-collar workers, the new crop of employees who created and used computers and other seemingly esoteric products.

The DNC shifting their attention from blue-collar workers in the industrial economy to white-collar workers in the information economy made for visionary policy and disastrous politics.

In the five presidential elections from 1972 to 1988, Republicans won four by an average of 11.2 million votes. Democrats won only once by 1.7 million, and that was in the wake of Watergate, the worst presidential scandal in more than a century.

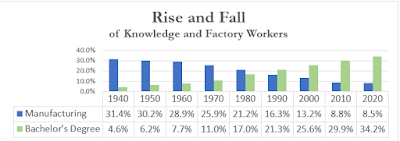

If you look at this graph, you can see that in 1970, manufacturing workers were 26% of the workforce. By contrast, college graduates were just 11%. If all you knew is that Republicans had a coalition that focused on factory workers and Democrats focused on knowledge workers and that factory workers outnumbered knowledge workers by more than 2 to 1, you would predict a huge victory for Republicans. And that is, indeed, what happened. In 1972, Nixon won by nearly 18 million votes. It was a landslide. In 1976, after Watergate, Carter won as a Democrat but in 1980, 1984, and 1988, Republicans won the White House.

In the five presidential elections between 1972 and 1988, Republicans won four by an average of 11.2 million votes and Democrats won one by 1.7 million.

By 1992, though, knowledge workers eclipsed factory workers. From then on, Democrats have convincingly won the popular vote.

In the seven presidential elections since 1992, Democrats have won four elections by an average of 7.1 million votes. Republicans have won three elections by an average of -133,444 votes. (Yep. That number is negative.) In those seven elections, Republicans won the popular vote only once and - like the 1976 election after Watergate - the 2004 election was in the wake of 9-11 and the invasion of Iraq. That is to say, like 1976, in 2004 voters thought something else mattered more than their economic interests.

In the seven presidential elections since 1992, Democrats have won four elections by an average of 7.1 million votes. Republicans have won three elections by an average of -133,444 votes. (Yep. That number is negative.) In those seven elections, Republicans won the popular vote only once and - like the 1976 election after Watergate - the 2004 election was in the wake of 9-11 and the invasion of Iraq. That is to say, like 1976, in 2004 voters thought something else mattered more than their economic interests.

From a policy perspective - a question of what policies will create the most jobs and wealth - we had easily moved into an information economy by 1972. From a political perspective - a question of what will get you elected - we had moved into an information economy by 1992.

I'm confident that Trump will not win the popular vote in 2020. I'm doubtful that he will again win the electoral vote. Too many urban residents who identify with and are a part of the global, diverse information economy dependent on knowledge workers will vote against him and not enough rural residents who identify with and are part of the national, industrial economy dependent on capital and factory workers will vote for him.

25 May 2019

The Most Underrated Inventions of the 20th Century?

Robert J. Gordon's Rise and Fall of American Growth includes some stunning statistics about the American workforce.

First, the 20th century saw an outbreak of fabulous inventions. The automobile, radio, and light bulb were among the inventions made in the 19th century that were popularized in the 20th century. Additionally, inventions like the airplane, the polio vaccine, and the computer originated in the 20th century. I don't think the best inventions of that century get enough credit, though.

In 1870, male labor force participation rate for those 65-75 was 88 percent. Before social security or the popularization of financial tools like pension plans and investment accounts, people essentially had to work until they died.

30% of boys 10 to 15 (and 50% of boys 14 to 15) also worked. And this is a formal count. More would have helped on family farms and not been counted. Kids had to quickly help with family finances. By 1940, this had dropped. Kids were in school instead.

Work changed too. The percentage of the workforce engaged in blue-collar work classified as operators (largely factory workers) and laborers held steady from about 1870 to 1970. Between 1970 and 2009, the percentage was halved to 11.6%. Meanwhile, workers engaged in "non-routine cognitive" work steadily rose from 8% in 1870 to 37.6% in 2009. The ratio of cognitive work to factory work rose from 0.4 to 3.2.

Work changed too. The percentage of the workforce engaged in blue-collar work classified as operators (largely factory workers) and laborers held steady from about 1870 to 1970. Between 1970 and 2009, the percentage was halved to 11.6%. Meanwhile, workers engaged in "non-routine cognitive" work steadily rose from 8% in 1870 to 37.6% in 2009. The ratio of cognitive work to factory work rose from 0.4 to 3.2.

Work that builds up our intelligence rather than breaks down our body is yet another great invention of the 20th century.

Along with all this, the workweek fell from 60 hours to less than 40.

Childhood and work are becoming more interesting and less grueling. We have retirement and two-day weekends. That is at least as cool as automobiles and smart phones. I would say that childhood, weekends, and retirement are the most underrated inventions of the 20th century.

First, the 20th century saw an outbreak of fabulous inventions. The automobile, radio, and light bulb were among the inventions made in the 19th century that were popularized in the 20th century. Additionally, inventions like the airplane, the polio vaccine, and the computer originated in the 20th century. I don't think the best inventions of that century get enough credit, though.

In 1870, male labor force participation rate for those 65-75 was 88 percent. Before social security or the popularization of financial tools like pension plans and investment accounts, people essentially had to work until they died.

30% of boys 10 to 15 (and 50% of boys 14 to 15) also worked. And this is a formal count. More would have helped on family farms and not been counted. Kids had to quickly help with family finances. By 1940, this had dropped. Kids were in school instead.

Work changed too. The percentage of the workforce engaged in blue-collar work classified as operators (largely factory workers) and laborers held steady from about 1870 to 1970. Between 1970 and 2009, the percentage was halved to 11.6%. Meanwhile, workers engaged in "non-routine cognitive" work steadily rose from 8% in 1870 to 37.6% in 2009. The ratio of cognitive work to factory work rose from 0.4 to 3.2.

Work changed too. The percentage of the workforce engaged in blue-collar work classified as operators (largely factory workers) and laborers held steady from about 1870 to 1970. Between 1970 and 2009, the percentage was halved to 11.6%. Meanwhile, workers engaged in "non-routine cognitive" work steadily rose from 8% in 1870 to 37.6% in 2009. The ratio of cognitive work to factory work rose from 0.4 to 3.2.Work that builds up our intelligence rather than breaks down our body is yet another great invention of the 20th century.

Along with all this, the workweek fell from 60 hours to less than 40.

Childhood and work are becoming more interesting and less grueling. We have retirement and two-day weekends. That is at least as cool as automobiles and smart phones. I would say that childhood, weekends, and retirement are the most underrated inventions of the 20th century.

20 May 2019

What I Forgot to Tell my Son on His Wedding Day

I gave a toast to Blake on his wedding Friday but managed to

lose my list of bullet points. I reconstructed them about

ten minutes before the toast, pocketed them, and then spoke. But it was only

after an evening of strong emotions and great conversations with old friends and friends freshly made that I remembered my main point.

Meditation magnifies.

Joseph Campbell said that we don’t need to learn how to

meditate. We meditate all the time. We meditate on how tight money is this

month or why she said that or whether

they think we were foolish to wear this outfit or which celebrities’ life we

covet.

Consciousness is like a radio dial that broadcasts a mix of fact and

fiction, fantasy and memory, hope and resentment, passing scenery and national

news. We can scan the dial and bounce from one thought to this perception to that

memory to another thought all day. We can scan but we tend to land on familiar

thoughts, our favorite stations. Those are our meditations.

Be aware. Don’t become a martyr for your mate. Your job isn’t

to dedicate your life to suffering for them. So when awful or even merely

annoying things come up, face them and deal with them. But resolve them and move

on. (Oh, and resolution may be realizing “that is part of the package of her.”)

Don’t meditate on the things that eat at

you. Don't plug your ears and chant "I can't hear you," to them either. Deal with bad things. Do meditate on what it is about her that you admire,

adore, or aspire to for yourself. Keep coming back to that happy station. This is not meditation as escape from the world but, rather, focus on and amplification of what is best in it.

Because whatever it is that you meditate on, whatever it is

that you come back to again and again, that will be magnified. If it is good,

that will seem bigger. If it is bad, that will seem bigger. Regardless of how wonderful or terrible it is, whatever you meditate on will seem like a much bigger deal than it actually is. And that will change what you talk about, how you act, and the ripple effect of your influence in life.

Face reality and deal with issues - both delightful opportunities to seize and ugly issues to resolve. And in between, magnify

what you want more of by meditating on what delights you.

15 May 2019

The Real Economic Debate (is not about socialism or capitalism)

The

big debate isn’t about whether we should have a socialist or capitalist

economy.

Depending on how you define those terms, socialism and capitalism are either essential or absurd.

Do you define capitalism as no different than a market economy? By socialism do you simply mean some mix of social security, public funding for healthcare, public education, and unemployment insurance? By those definitions, capitalism and socialism are essential.

Or by capitalism do you mean that we should be rid of social security, healthcare, public education and unemployment insurance? And when you say socialism do you mean that we should do away with markets? By those definitions, socialism and capitalism are absurd and harmful.

It’s a valid thing to argue where on the spectrum between cruel market or controlling government we should be, but that can easily distract us from a more vital, more concrete debate about how normal people are going to create new jobs and wealth.

The debate about whether we're in an industrial or information economy is the more relevant and productive one. Put more simply, do we think that jobs and wealth are going to be created in factory work or knowledge work?

Depending on how you define those terms, socialism and capitalism are either essential or absurd.

Do you define capitalism as no different than a market economy? By socialism do you simply mean some mix of social security, public funding for healthcare, public education, and unemployment insurance? By those definitions, capitalism and socialism are essential.

Or by capitalism do you mean that we should be rid of social security, healthcare, public education and unemployment insurance? And when you say socialism do you mean that we should do away with markets? By those definitions, socialism and capitalism are absurd and harmful.

It’s a valid thing to argue where on the spectrum between cruel market or controlling government we should be, but that can easily distract us from a more vital, more concrete debate about how normal people are going to create new jobs and wealth.

The debate about whether we're in an industrial or information economy is the more relevant and productive one. Put more simply, do we think that jobs and wealth are going to be created in factory work or knowledge work?

*********************

College education has become one of the better predictors of

how people vote. In the 50 counties with the highest levels of education,

Hillary Clinton won by 26 percentage points. In the 50 least educated counties,

she lost by 31 percentage points.[1]

Those knowledge workers are also more affluent than factory workers. Clinton

won only one-third of the counties in the US but those counties represent about

two-thirds of the country’s GDP.

By contrast, Trump won by nearly 16 percentage points in the

ten states with the highest percentage of manufacturing workers and lost by 9

points in the ten states with the lowest percentage.

In 1972, the Democratic Party shifted its focus from factory workers to knowledge workers. In

1972, the Democratic National Committee had set quotas for women, minorities

and youth but none for blue-collar workers. In terms of policy, that was visionary. Since that time an information economy has clearly driven economic growth. In terms of politics, it was disastrous. Knowledge workers still made up only 11% of the population in 1970. Democratic

nominee George McGovern lost by 520 to 17 electoral votes in 1972 and in 1984,

Mondale won only 13 electoral votes.

Since 1992, college grads have outnumbered factory workers

and since 1992, Democratic presidential candidates have won the popular vote by

an average of 4.1 million votes (and only lost the popular vote once in the

last seven elections). In the Democrats’ last three presidential victories

(Obama 2012 and 2008, Clinton 1996), they won the popular vote by a total of

22.7 million. In the Republicans’ last three presidential victories (Trump

2016, Bush 2004 and 2000), they lost the popular vote by a total of 400,331.

Because of the quirk of the electoral college and knowledge workers’ tendency

to cluster in cities, Republicans and Democrats have split the last six

elections in spite of Democrats dominating the popular vote.

***************

Trying to bring back manufacturing jobs makes about as much sense as trying to bring back farming jobs. And for a host of reasons it simply isn't smart policy. Ours would not be a better economy if we still had 90% of the workforce engaged in raising crops for us nor would it be a better world if we still had 36% of the workforce making stuff. We can now be fat and our houses be cluttered with less than 2% of the workforce raising our food and 8% making our stuff.

The question is not "How do we get more people back into factories?" The question is, What work will add value, what work will actually improve our quality of life, what work would voters value enough to fund with government spending or consumers value enough to fund with cash or credit? That is the question entrepreneurs ask.

The answer to the question of whether we think that jobs and wealth are going to be created in factory work or knowledge work has two parts. Short-term, none will be created in factories but many will be created in knowledge work. (And by none I mean net. New jobs will emerge in factories but not as quickly as they are destroyed.) Long-term, all will be created by entrepreneurs.

We don't exactly have all our problems solved as yet. In every direction we turn there are problems to solve and possibilities to explore. How do we create affordable housing in big cities without creating more congestion? How do we increase the quality of life of people over 80? (The fastest growing group in the world.) How do we create institutions that encourage the intrinsic motivation that makes us happy, creative, and productive? How do we automate more of the tasks that have become boring and simply reduce our quality of life and create the tasks in their place that both create value for customers and flow for workers?

Wasting effort on returning to the past is like a 60 year old dressing like a 16 year old. What was once exciting has become disconcerting, what was great becomes caricature.

07 May 2019

Overeducated Workers in a Post-Information Economy

The simplest statement of effective economic policy is to create, get, or get more from whatever limits progress. As a community shifts from one economy to another (from, say, an agricultural to industrial economy), the limit shifts and so does effective policy.

All that as prelude to summarizing a report recently released by the UK's Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Here are some excerpts of note:

Overeducation is a form of mismatch where a person can be overeducated if they possess more education than required for the job.

Levels of overeducation: completed

before 1992: 21.7%;

1992-1999: 23.4%;

2000-2006: 24.8%;

2007 or after: 34.2%

The wage of an overeducated worker is between 3.3% and 8.1% lower compared to the wage of a worker with a similar level of education who is matched to the right occupation.

We find that overeducated graduates experience negative returns to overeducation.

Overeducation is becoming more prevalent and overeducated graduates actually get negative returns on their education.

I have not seen a similar report on American workers but have little doubt that it would tell a similar story.

We still imagine we're living in a world in which capital and knowledge workers limit progress and we put trillions into capital gains tax cuts and education funding .... even as those no longer limit.

03 May 2019

What a Shrinking Labor Force Means for the Job Market & the Economy

Since December, the labor force has shrunk by 770,000. This is one reason that the unemployment rate hit its lowest in this century in March. (It's been half a century since unemployment was at 3.6%.) This fall in labor force could be random variation but it may be a sign of a trend.

As you can see in this graph, the rate of growth in the labor force has been steadily falling in the last 5 decades.

Baby boomers and immigrants drove a big rise in the labor force. LBJ's Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965 ended the fairly racist quotas for immigration and increased the number of immigrants about the same time that baby boomers entered the job market. The birthrate for a stable population is about 2.1 births per woman. In 1960, the US had a birthrate of 3.65 and in 1973 it fell below 2, where it has stayed since.

The number of kids coming of age and the number of immigrants coming to our country have both steadily dropped since the 1970s. It is conceivable that in the 2020s, the labor force will actually stop growing.

This is good news for workers. Sort of. It should be mean strong wage growth for the millennials whose careers started out in the midst of the Great Recession. Workers will have more power in negotiations with companies who are competing for a shrinking pool of workers. They deserve it and it could be good for their pocketbooks. This also suggests that house prices will increase at a slower rate as demand for housing eases.

The news is not as good for the economy for at least two reasons.

The most obvious is that the ratio of retired to those working will go up. That suggests more poverty among the retired than we'd otherwise have. (Baby boomers might care about this.) Elder care will be more expensive as wages rise.

Less obvious is what fewer workers mean for an economy.

Just today the New York Times published a story on how Hungary's economy is now limited by workers. Prime Minister Viktor Orban is, like Trump, an anti-immigrant nationalist. Hungary is not the only European country experiencing lower birthrates, though. Demand for workers is up throughout much of Europe. Because of this, Hungarian workers are leaving for better paying jobs in big European cities. So Hungary's labor shortage is driven by two things: its own people emigrating to other countries and other people not immigrating into Hungary. As a result, businesses are turning away orders because they cannot fill them.

How are we i the US doing with immigration as birthrates fall?

Foreign student enrollment in American universities has fallen two years in a row - essentially since Trump has taken office. The immigrants we should most want - those able to get into our universities - are choosing to go elsewhere, raising the probability they will go work elsewhere.

There is something else going on here that rarely gets mentioned. As population increases, so does per capita GDP. More people stimulate more ideas, more creativity, more products, more technologies, and more businesses. This is a big reason why productivity and wages are so much higher in cities than in rural areas. Our creativity is stimulated by interactions with people; and the more diverse that group, the more creative our response.

The good news about diminishing growth in the labor force is that it will mean that workers will likely get more of the pie, be able to negotiate higher wages this year. The bad news is that there will be less pie, less creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship than we'd have with a larger, more diverse population and wages - while taking a higher percentage of corporate revenue - could actually be lower than they otherwise would be. (And that, of course, suggests company earnings would be smaller for two reasons: smaller portion of revenues going to profit and smaller revenues.)

As birthrates fall across the West, smart countries will compete for immigrants, not shun them. Us? Well, apparently we're cashing in our lead in immigration and choosing to become more like Hungary.

As you can see in this graph, the rate of growth in the labor force has been steadily falling in the last 5 decades.

Baby boomers and immigrants drove a big rise in the labor force. LBJ's Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965 ended the fairly racist quotas for immigration and increased the number of immigrants about the same time that baby boomers entered the job market. The birthrate for a stable population is about 2.1 births per woman. In 1960, the US had a birthrate of 3.65 and in 1973 it fell below 2, where it has stayed since.

The number of kids coming of age and the number of immigrants coming to our country have both steadily dropped since the 1970s. It is conceivable that in the 2020s, the labor force will actually stop growing.

This is good news for workers. Sort of. It should be mean strong wage growth for the millennials whose careers started out in the midst of the Great Recession. Workers will have more power in negotiations with companies who are competing for a shrinking pool of workers. They deserve it and it could be good for their pocketbooks. This also suggests that house prices will increase at a slower rate as demand for housing eases.

The news is not as good for the economy for at least two reasons.

The most obvious is that the ratio of retired to those working will go up. That suggests more poverty among the retired than we'd otherwise have. (Baby boomers might care about this.) Elder care will be more expensive as wages rise.

Less obvious is what fewer workers mean for an economy.

Just today the New York Times published a story on how Hungary's economy is now limited by workers. Prime Minister Viktor Orban is, like Trump, an anti-immigrant nationalist. Hungary is not the only European country experiencing lower birthrates, though. Demand for workers is up throughout much of Europe. Because of this, Hungarian workers are leaving for better paying jobs in big European cities. So Hungary's labor shortage is driven by two things: its own people emigrating to other countries and other people not immigrating into Hungary. As a result, businesses are turning away orders because they cannot fill them.

How are we i the US doing with immigration as birthrates fall?

Foreign student enrollment in American universities has fallen two years in a row - essentially since Trump has taken office. The immigrants we should most want - those able to get into our universities - are choosing to go elsewhere, raising the probability they will go work elsewhere.

There is something else going on here that rarely gets mentioned. As population increases, so does per capita GDP. More people stimulate more ideas, more creativity, more products, more technologies, and more businesses. This is a big reason why productivity and wages are so much higher in cities than in rural areas. Our creativity is stimulated by interactions with people; and the more diverse that group, the more creative our response.

The good news about diminishing growth in the labor force is that it will mean that workers will likely get more of the pie, be able to negotiate higher wages this year. The bad news is that there will be less pie, less creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship than we'd have with a larger, more diverse population and wages - while taking a higher percentage of corporate revenue - could actually be lower than they otherwise would be. (And that, of course, suggests company earnings would be smaller for two reasons: smaller portion of revenues going to profit and smaller revenues.)

As birthrates fall across the West, smart countries will compete for immigrants, not shun them. Us? Well, apparently we're cashing in our lead in immigration and choosing to become more like Hungary.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)