The

definition of work changes as economies evolve. The grandchildren of farmers became factory workers and the grandchildren of factory workers became knowledge workers. There’s good reason to believe

that the definition of employee will change again, this time into something

like entrepreneurship.

Thomas

Jefferson imagined the United States as a country of educated, gentleman

farmers. Even when he became president in 1801, though, the percentage of Americans

farming had begun its steady decline. Now, each month economists await the

announcement of nonfarm payroll employment. Today farm jobs are not even

included in the country’s defining measure of jobs lost and gained.

Alexander

Hamilton’s vision of an industrialized nation turned out to be more prescient

but in recent decades, manufacturing’s share of the work force has also been in

steady decline. Next century, economists may await the nonmanufacturing payroll

employment report.

Millions

voted for Trump and his promise to bring back manufacturing jobs. As promises

go, it seems more akin to a 1916 campaign promise to bring back farming jobs

than an adaptation to new realities. Yet acknowledging that farming and

manufacturing are unlikely to reverse their decline leaves us with the question

about the source of next generation jobs.

------------

The economy has shifted but policy has not. Until economic policy begins to address the new limit, it will continue to be ineffective.

Over the last 40 or 50 years the per capita GDP growth rate

has fallen. The fallout is not just economic. It has made voters less trusting

of major institutions and expressed itself in surprising victories for BREXIT

and Trump. Most people now feel that “the system is broken, unfair, and failing

them.”

Meanwhile, one place that has done remarkably well in the

last half century is Silicon Valley, a place that more than any other has

become synonymous with entrepreneurship.

About a century ago, Henry Ford made business history by

doubling the wages of his factory workers. Doubling. Not only was he making

cars more affordable, he was paying working class people enough to buy them.

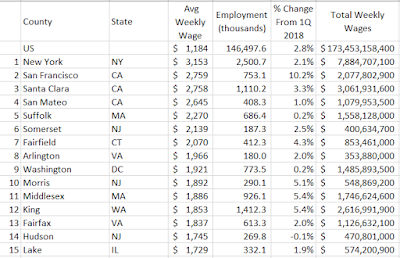

In 2016, median wages in the US were about $51,000 a year. Like

Ford, Silicon Valley has doubled that. In Santa Clara County – one reasonable

approximation of Silicon Valley – average wages were $117k, or 118% higher than

the national average.

It’s possible that Silicon Valley is an anomaly, a place that

other communities can only envy but never emulate. A more interesting

possibility is that Silicon Valley is to a new entrepreneurial economy what

Manchester, England of the 1700s was to a new industrial economy: just the

first place to enter a new economy whose practices will eventually spread around

the world.

Four

Economies and Four Limits

Agricultural economies give way to industrial economies,

which give way to information economies. Most people share that intuition but their

understanding of what these labels mean and how to distinguish between them is

fuzzy. Even industrial economies have farms and information economies have

factories. It takes a little explanation, but limits can clarify the distinction

between different economies and predict a fourth, entrepreneurial economy.

Economy

|

Period in West

|

1st, Agricultural

|

1300 to 1700

|

2nd, Industrial

|

1700 to 1900

|

3rd, Information

|

1900 to 2000

|

4th, Entrepreneurial

|

2000 to ~

|

Before talking about economies, imagine a factory with four stages.

It gets raw materials in on one end and sends product out the other. The

materials that become a finished product must pass through all four stages

before they’re sold.

The numbers and height of the bar indicate how many products

a stage can process in an hour. The first stage can process only 1, the second

can process 2 and the fourth and final stage has the capacity to process 4

products an hour.

The customers don’t buy the unfinished product from any intermediate

phase, though. They only buy product that comes out of the whole factory,

product that has passed through all four phases. The question is, what is the

capacity of this whole factory? How many products can it produce per hour?

The answer is 1 per hour. Your factory’s capacity is equal

to the capacity of your first stage. You could call that a bottleneck, a

constraint or limit. Whatever you call it, this limit defines the capacity for

your whole factory. If it can only feed the next stage 1 item per hour, it

doesn’t matter that the second stage has the capacity to process 2 items per

hour because it won’t get product fast enough to process that many.

Until you increase the capacity of the first stage, you will

not increase the capacity of your factory. So, you experiment. Maybe you speed

up the process, simplify the process or just buy a second machine for that first

stage. However you do it, you eventually double the capacity of this first

stage to get a picture like this:

The good news is that by doubling the capacity of the first

stage you have just doubled output for the whole factory. Armed with the

knowledge that focusing on the first stage makes all the difference, you

continue to experiment and invest in improving that first stage until you find

a way to double its capacity again.

This time, though, doubling the capacity of your first stage

does not change your factory output. Why? You were so successful at improving

the first stage that it is no longer the limit to your factory. Your limit has

shifted elsewhere.

Two lessons from your factory could apply to any system.

- To improve the system, you have to focus on the

limit, and

- Success eventually shifts the limit.

So, what limits an economy? In every introductory economics

course, students learn that there are just four factors of production: land,

capital, labor, and entrepreneurship. Anything of value created by an economy

depends on some mix of these four factors and one of those would have to be the

limit at any given stage of economic development. Land includes all natural

resources, from herring to oil, acreage and cotton. Capital includes the

financial and industrial tools that transform those natural resources into

finished products, the factories that can turn cotton into clothing and the

stocks or bonds that finance the machines and factories. After the industrial

revolution, the labor of knowledge workers – people like accountants, engineers

and advertisers – who manipulate the symbols of things rather than actual

things was the most defining labor. Finally, entrepreneurship brings together

land, capital and labor into a profitable enterprise.

The four phases of a factory can become four factors of

production in an economy and we can examine limits to an economy in the same

way that we examined limits to the factory. The output of an economy can be

measured by things like jobs or wealth, income or GDP.

Different

limits create different economies

Agricultural economies are limited by land. Wealth between

1300 and 1700 didn’t result from advances in information technology (not that

the Gutenberg Press wasn’t disruptive) but instead came from trade, conquest,

and colonization with faraway lands and creating nation-states and private property

in your own land.

An industrial economy is limited by capital. Between 1700

and 1900, the creation of wealth was less about exploration, conquest and

colonization than it was about building the factories that could turn raw

materials into finished goods and then build out canals and railroads to

distribute those goods. Wool and cotton became fashion. Iron ore became

railroads. Skyscrapers rose in cities and cars emerged to drive between them.

An information economy is limited by knowledge workers.

Between 1900 and 2000, it wasn’t enough to have factories that could make more

products than anyone had ever seen before. They had to be the right products (which

required marketing and design expertise) made for and sent to the right places (which

took manufacturing and distribution knowledge) by the right methods (which took

advertising and retail display experts.)

An information economy emerges after an industrial economy.

Before the automation of the industrial economy, you need workers to manipulate

actual things, afterwards, machines can do that and labor can shift its focus to manipulating

symbols. The sequence from agricultural to industrial to information economies

is not just an historical sequence, it’s a logical one.

Economy

|

Limit

|

Period in West

|

1st, Agricultural

|

Land

|

1300 to 1700

|

2nd, Industrial

|

Capital

|

1700 to 1900

|

3rd, Information

|

Knowledge Workers

|

1900 to 2000

|

4th, Entrepreneurial

|

Entrepreneurship

|

2000 to ~

|

Economies are complicated and progress is slow so it makes

sense that as communities gradually overcome limits they’ll cling to the

processes that once made them great. Like the factory manager who keeps

doubling the capacity of his first process step to no avail, communities can continue

to create foreign colonies, spending huge sums on a global empire even after

they’ve entered an industrial economy. Or more recently, they might pump money

into their economy or create graduates past the point that capital or knowledge

workers actually limit the rise in per capita GDP. It is almost inevitable that

communities will continue to do what they’re now good at even after reaching a

point of diminishing benefit. Cultures last longer than cost-benefit analysis

and new practices become old habits.

An additional complication is that there are always pockets

within a larger community that face earlier limits, and those limits define local

culture and politics. When natural resources are the basis for wealth in a

region, for instance, it will be more religious and more inclined towards

policies like a strong military that support the notion of a zero-sum economy.

It’s not the ingenuity of people that creates an oil field but is instead just

a gift of God or nature. And that oil field doesn’t get larger because we

decided to share it. Either I own it or you do, and rather than win-win we’re

going to have a winner and a loser in this exchange. There will always be

regions that lead or lag in development and thus will lead or lag in the reality

they experience and that informs their convictions. It’s not just that a person

living in rural Kentucky has a different political philosophy than her peer in

Cambridge, MA; the daily reality that informs her perspective is different.

One other way to understand a limit is to look at its price.

Scarce factors are expensive and abundant factors are cheap.

The success of the second economy made capital abundant.

Traditional bankers who emerged from the second economy (many of our current

banking practices were defined in England by 1900) carefully loaned out money,

trying to minimize the risk of losing capital. Venture capitalists, by

contrast, treat capital as abundant and fully expect to lose quite a few

investments. Given they’re taking equity in a new firm rather than hoping to

get back capital with interest, they know that only a fraction of their

investments need to succeed in order for them to get great returns. Traditional

banking evolved when capital was scarce: venture capitalists evolved when

capital was abundant.

What is scarce now? Entrepreneurship and we can see that in

its price. At 31, Bill Gates became the richest self-made billionaire in

history. A generation later, Mark Zuckerberg became a billionaire at 24. The

price of capital is the interest rate and towards the end of last year,

investors owned about $12 trillion in negative interest rate bonds. Trillion. We

have a glut of capital and a shortage of entrepreneurs, which suggests that

effective policy would focus on increasing the supply of entrepreneurs rather than

the supply of capital. Between 1700 and 1900, we learned how to increase the

supply of capital through a variety of means, from popularizing savings and

investment (from founding father proverbs like “A penny saved …” to expanding the

number of people who bought wartime bonds and then later became savers) to

changing the money supply or interest rates. If policy makers think that we’re

short of capital, they can quickly pump billions into the economy. There are no

comparable policy levers for increasing levels of entrepreneurship. Not yet.

When The

Old Limits No Longer Limit

If capital were still a limit, we’d be in great shape. The

S&P 500 have $1.5 trillion in cash and in the third quarter of last year

they paid out $200 billion in dividends and stock buybacks. Banks excess

reserves have dropped from their August 2014 high of $2.7 trillion but are

still at a staggering $1.9 trillion.

(Before the Great Recession, excess reserves in the US were closer to $1.5

billion.)

Our education system helped us to overcome the limit of

knowledge workers. In 1900, less than 10% of 14 to 17 year olds were formally

enrolled in education. By 2000, less than 10% were not. In a century, the US

went from an industrial economy dependent on child labor to an information economy dependent on adult education. That helped to transform life in the 20th

century, real incomes increasing 6X to 8X and life expectancy rising from 47 to

77.

If knowledge workers and their information technology were

still a limit, creating more graduates would help to create more jobs. In 2013,

the American education system created 3.7 million graduates, everything from

folks with AA degrees to PhDs and all the degrees in between. That same year,

the economy ended the year with 2.4 million more jobs than it had at the start.

We’re creating graduates faster than we’re creating jobs, 15 new graduates for

every 10 net new jobs. It’s no wonder that student debt is becoming a growing

issue.

It’s not just ineffectual to pursue old policies in a new

economy. It can be dangerous.

A glut of money creates problems. Investors in search of

returns, unwilling to accept negative interest rate bonds, too readily bought expensive

things like tech stocks in 1999 or subprime mortgage instruments in 2007. Trillions

in investments can create a series of bubbles and busts as it wanders the earth

like a murmuration of starlings in search of returns.

A glut of graduates creates problems. Young people not only

start careers with mounting debt but find it more difficult to find jobs they

could not have worked with just a high school diploma. Millennials who are the best-educated

generation in history nevertheless fear that they’ll be the first generation in

American history to do worse than their parents. (This student debt will also

make it tougher for them to finance startups. As medical school has become more

expensive, for example, the percentage of doctors working for large groups or

hospital has gone up relative to those who start a private practice.)

One consequence of continuing to pursue dated policies is

that it makes it tougher to pursue any policy. When incomes are steadily

rising, politics is civil. Families can pay a little more in taxes to support schools

and help the poor while still taking home more pay after taxes. When incomes

are stagnant, politics becomes more divisive. Few people like the idea of not

supporting education or the sick but if the choice is between that or less take

home pay? Well, the conversation becomes more heated and compromise is harder

to reach on top of the fact that everyone starts this policy conversation

disenchanted and bewildered.

We don’t need to jettison incredible financial and

educational systems that are essentially over-producing, creating more capital

or graduates than we can fully employ. We just have to stop looking to those

systems as the means to create jobs and wealth. As we become successful at

overcoming this new limit of entrepreneurship, we’ll be able to fully employ

capital and college grads. Eventually, we will even create enough demand for

them to bid their prices up further.

The Central

Question of Every Economy

The central question for any generation concerned about

economic progress is how to overcome its limit, not the limit of its

grandparents or founding fathers. Creative answers to that question result in a

new economy and a very different community.

In retrospect, the central question of economic development

from about 1700 to 1900 was simple: how do we get more capital and make it more

productive? The creative answers to this included everything from the Dutch

stock market, Rothschild’s international bond market and the British banking

system to the spinning jenny, steam engine, and continuous production

technology. (The question is simple. The answers can be complicated.)

The central question of last century was, how do we create

more knowledge workers and make them more productive? The creative answers to

this included the popularization of K-12 education, the modern university,

R&D labs, the modern corporation and information technology.

The question that policy makers everywhere – city hall and

senate floor, corporate boardrooms and universities – should now ask has two

parts:

- How do we create more entrepreneurs and make

them more effective?

- How do we make employees more entrepreneurial?

Creative answers to these simple questions will transform the

economy. We now have a financial system and an education system. We don’t have

an entrepreneurial system but instead expect our entrepreneurs just to show up,

like autodidacts in 1800. Changing will be an odd, fascinating and profitable

project. Think about educating students to be prepared to become entrepreneurs

in the same way that we now educate students to become university students and

knowledge workers, for instance, or changing the definition of employee.

Changing

the Definition of Work. Again.

Perhaps more interesting than the question of how to create

more entrepreneurs is the question of how to make employees more

entrepreneurial. We – rightfully – make a big deal about national economic

policy. It’s worth keeping in mind that measured by GDP or revenue, of the 100

biggest economic entities only 31 are countries; the other 69 are corporations.

(Walmart’s $480 billion in revenue would put it just between Sweden and Belgium’s

GDP.) Corporate policy deserves as much discussion as national policy if we’re

interested in progress. The most important topic in this discussion might be to

ask what it means to be an employee in a time when AI like IBM’s Watson is

liable to automate knowledge work in the same way that capital automated manual

work.

Think about changing employment so that employees within a

corporation had as much freedom to pursue new ventures as citizens within a

country. Roughly 800,000 Americans make more than the $400,000 a year that we

pay the president.

That sort of thing was unthinkable in Egypt under Hosni Mubarak or France under

King Louis XIV, but as nation-states evolve, people within them have the

potential to prosper more than even the head of state. Contrast that with how

evolved the corporation is. While it’s common for professional athletes or

portfolio managers to make more than their managers, it is rare that anyone

inside a traditional Fortune 500 firm makes more than the CEO. What if

employees could become more entrepreneurial, were able to create equity by

taking existing products into new markets or by leading product and business

development efforts that are akin to startup activities? And what if the

success of those ventures could actually result in their making more than the

head of the company in the same way that an American entrepreneur has the

potential to make more than the American president? This dispersion of power

and pay is just one way that the popularization of entrepreneurship will change

the corporation.

Overcoming the limit of entrepreneurship will require and

result in new legislation, new education, and new definitions of what it means

to be an employee. As importantly, it will continue in a grand tradition of the

west, doing for business what earlier economies did for religion, politics, and

finance. That is, it will expand freedom for the individual. There is no way to

make employees more entrepreneurial without giving them more freedom.

There are interesting examples of popularizing

entrepreneurship within companies. Ricardo Semler did something interesting

with his Brazilian company Semco. He gave his employees freedom to negotiate

work arrangements. People working side by side on the factory floor doing

similar work might have very different arrangements. One was paid hourly,

another a monthly salary, another paid by piecework and another might actually

be paying Semco to use equipment to make product that she – the employee – could

later sell herself. Uber lets “employees” accept or reject specific fares and take

just one fare a week or work all day. Amazon’s marketplace and Apple’s iTunes

are platforms that let companies and entrepreneurs sell their own products. P&G

is among the companies who richly reward successful product development leads

whose responsibilities overlap quite a bit with entrepreneurs. All of these are

examples of enabling entrepreneurship, blurring the boundary between

traditional definitions of employee and entrepreneur, and giving the employee

more freedom to define their own work and its results.

This matter of employees gaining more autonomy is not

incidental to progress. Autonomy is a way to define progress and each new

economy has given the individual in the West more freedom. If you have shoes

you have more options about where to go than if you are barefoot; if you have a

car you have even more options. If you live in a democracy, you have more

options about what to believe and how to live than if you live in a theocracy.

If you have a credit card you have more options than if you need to approach a

banker to request a loan for a specific item, or can’t get a loan at all. If

you have the freedom to create equity as an employee you have more freedom than

if you’re expected to adhere to a process someone else defined.

The popularization of entrepreneurship will increase our

product options and levels of wealth. Progress, though, is only partly about

more and better products. That is only one way that our lives expand to include

more options. The first economy didn’t just bring potatoes and tomatoes to

Europe; it brought religious freedom. The second economy didn’t just bring fashion

and automobiles to households; it brought democratic freedoms. And the third

economy didn’t just give us radio and the polio vaccine; it made capitalists out

of knowledge workers, giving them financial options that people in 1900 would

have found as baffling as the internet. The fourth economy will transform business

and work in the same way that the first three economies transformed religion,

politics, and finance. That is, it will give us more autonomy, as economic

progress always does.

As you might imagine, there is a great deal more to this new economy than would can be captured here. My book, The Fourth Economy: Inventing Western Civilization, can be found

here. It's a longer read but it does explain progress from the Dark Ages to about 2050.