There is so much more to a president's approval rating than just the rate at which the economy created jobs during his term. His looks, for instance. Or his committing criminal acts, starting wars, giving speeches, or kicking off popular or unpopular programs. The graph below ignores all of that and just plots approval rating at the end of an administration (or, obviously, most recently for Obama) against the average annual job creation rate.

If you draw a line from George W. Bush's low approval rating and low job creation average to Bill Clinton's high approval rating and high job creation average, Obama pretty much lands neatly on that line between them. Judging just from how well the economy did at creating jobs, Carter's approval seems unjustly low and George H. Bush's approval seems unfairly high.

What can you say about America's opinion of Obama? Just based on this simple metric, it seems fair enough, even if the job creation numbers would be closer to what they were under Reagan had he not taken office just as the worst recession in a century was gaining momentum.

30 April 2016

What if the Republican Party is Simply Obsolete?

Republicans continue to fantasize about a last-minute candidate emerging from the Republican convention who the country will love. As if they didn't have quite a smattering of strong candidates among their original 17.

The problem is not that they don't have good and decent people with proven legislative and governing experience. The problem is that the policies that excite them are going the way of opposition to women voting and regulating pollution.

What beliefs define Republicans? Belief that the rich need more tax breaks and the poor need less help. Belief that women should not be the ones to make a decision about whether to terminate a pregnancy or even use contraceptives. Belief that climate change is a huge conspiracy. Belief that businesses are unduly burdened by regulations that make it difficult for them to pollute. (Cruz wants to eliminate the EPA.) Belief that the government should be cut by about half, made less effective at educating a workforce as education is becoming increasingly important, made less effective at offering a social safety net as the population becomes older than ever and as the economy becomes more risky than ever. Belief that American bombs and boots on the ground are the solution for so many of the problems facing regions like the Middle East that are going through huge and often violent change. Belief that morality is inseparable from religion.

Now you might share all of these beliefs and convictions. If you do, you're likely old and will likely vote in only two or three more presidential elections. The Silent generation (now age 69 to 86) tilts Republican by about 4 points. By contrast, the Millennial generation (age 18 to 33) tilts Democrat by 16 points. Every presidential election, 2016 to 2020 to 2024 ... this will make it harder for Republicans to win.

To raise voter turnout, Republicans have made an even bigger deal about their beliefs in recent elections. Higher turnouts helped them to elect and re-elect George W. Bush but it also solidified their position as the party with these beliefs. Both in branding and execution. When the Bush / Cheney tax cuts failed to create jobs, their de-regulation failed to make the economy more robust, and their military invasions failed to create a shining example of democracy in the Middle East, those beliefs were called into question. Napoleon gets credited with the quip, "Tell me what the world was like when you were 18 and I'll tell you your worldview." Polls suggest that Millennials were not impressed with the world they came into as young adults, or the beliefs that shaped it.

So the question is, does the Republican Party have a hope of changing their beliefs and their image for Millennials Or more precisely, will it be easier for them to make this change than it will be for a new party to emerge. Because no matter how strongly you believe in the beliefs of the party represented by Ted Cruz and Donald Trump, you are in a dwindling minority. The only question is whether the Republican Party of 2032 will have become a regional party with just pockets of success in the south and midwest or whether it will look radically different than it does now, espousing very different beliefs than those that Cruz and Trump are using to rally their followers.

The problem is not that they don't have good and decent people with proven legislative and governing experience. The problem is that the policies that excite them are going the way of opposition to women voting and regulating pollution.

What beliefs define Republicans? Belief that the rich need more tax breaks and the poor need less help. Belief that women should not be the ones to make a decision about whether to terminate a pregnancy or even use contraceptives. Belief that climate change is a huge conspiracy. Belief that businesses are unduly burdened by regulations that make it difficult for them to pollute. (Cruz wants to eliminate the EPA.) Belief that the government should be cut by about half, made less effective at educating a workforce as education is becoming increasingly important, made less effective at offering a social safety net as the population becomes older than ever and as the economy becomes more risky than ever. Belief that American bombs and boots on the ground are the solution for so many of the problems facing regions like the Middle East that are going through huge and often violent change. Belief that morality is inseparable from religion.

Now you might share all of these beliefs and convictions. If you do, you're likely old and will likely vote in only two or three more presidential elections. The Silent generation (now age 69 to 86) tilts Republican by about 4 points. By contrast, the Millennial generation (age 18 to 33) tilts Democrat by 16 points. Every presidential election, 2016 to 2020 to 2024 ... this will make it harder for Republicans to win.

To raise voter turnout, Republicans have made an even bigger deal about their beliefs in recent elections. Higher turnouts helped them to elect and re-elect George W. Bush but it also solidified their position as the party with these beliefs. Both in branding and execution. When the Bush / Cheney tax cuts failed to create jobs, their de-regulation failed to make the economy more robust, and their military invasions failed to create a shining example of democracy in the Middle East, those beliefs were called into question. Napoleon gets credited with the quip, "Tell me what the world was like when you were 18 and I'll tell you your worldview." Polls suggest that Millennials were not impressed with the world they came into as young adults, or the beliefs that shaped it.

So the question is, does the Republican Party have a hope of changing their beliefs and their image for Millennials Or more precisely, will it be easier for them to make this change than it will be for a new party to emerge. Because no matter how strongly you believe in the beliefs of the party represented by Ted Cruz and Donald Trump, you are in a dwindling minority. The only question is whether the Republican Party of 2032 will have become a regional party with just pockets of success in the south and midwest or whether it will look radically different than it does now, espousing very different beliefs than those that Cruz and Trump are using to rally their followers.

Sweden Stops Wrinkling its Nose at Entrepreneurship

I rode home beside a lovely man from Sweden the other day. He now lives in San Diego, helping to manage a start-up.

He told me that even ten or fifteen years ago, people in Sweden wrinkled up their nose at entrepreneurship. "Oh. You couldn't get a real job, eh?"

Now he says, the success of Skype and Spotify have changed their opinion. "It's a country of only 9 million, so it doesn't take long to change popular opinion."

And to my ears, this is just one more example of how the West is slowly popularizing entrepreneurship.

He told me that even ten or fifteen years ago, people in Sweden wrinkled up their nose at entrepreneurship. "Oh. You couldn't get a real job, eh?"

Now he says, the success of Skype and Spotify have changed their opinion. "It's a country of only 9 million, so it doesn't take long to change popular opinion."

And to my ears, this is just one more example of how the West is slowly popularizing entrepreneurship.

An Excerpt from The Fourth Economy (on this, Claude Shannon's 100th birthday)

My book The Fourth Economy includes the stories of Henry VIII and Henry Ford, Pope Boniface and Andrew Carnegie, Galileo and Wilhelm Humboldt. To be mentioned in this book that covers 700+ years of history is a big deal. Claude Shannon - who today Google is honoring for his 100th birthday - made the cut. Here's an excerpt from the book in a section explaining the third, information economy, that includes mention of Shannon.

Knowledge Workers Create IT for Knowledge Workers

The Summer of Pocket Protectors

Knowledge Workers Create IT for Knowledge Workers

Bell Labs – named after AT&T founder Alexander Graham

– employed 25,000 employees at its peak, including 3,300 PhDs.[1]

Bell Labs was a paragon of knowledge work, a place where people were paid to

think. In 1947, the lab produced two innovations that became the paragon of

information technology.

The first innovation was conceptual. Claude Shannon coined

the word “bit” in an attempt to do something no one had ever done. His was the

first attempt to quantify information. With the right pattern, 1 and 0 could be

used to describe any letter or number (a combination that would come to be

known as a byte). This was interesting.

Then, in that same year, Bell Labs produced another

innovation that would – when coupled with Shannon’s bit – enable the computer.

Three of its employees would eventually share a Noble

Prize for inventing a product Bell Labs thought might might “have far-reaching

significance in electronics and electrical communication."[2]

The transistor was a simple replacement for the bulky vacuum tubes and given it

could easily be turned on or off, it could easily be made to represent a 1 or 0

– a bit.

By the 1960s, multiple transistors were joined together on

a computer chip, the heart of a computer. No invention would better define

information technology.

Yet even with the advent of this new technology, something

was missing. Technological invention alone is rarely enough; to make real gains

from the computer chip required social invention, a change in corporate

culture.

One of the three co-inventors of the transistor began a

company to exploit this new technology.

William Shockley (1910-1989) was co-inventor of the

solid-state transistor and literally wrote the book on semiconductors that the

first generation of inventers and engineers would use to advance this new

technology. He had graduated from the best technical schools in the nation (BS

from Cal Tech and PhD from MIT), and was the epitome of the modern knowledge

worker.

Shockley hired the best and brightest university graduates

to staff his Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory. Yet things were not quite right.

It was not technology, intelligence, or money that his company lacked. It was

something else.

To answer what it was leads us to the question of why

information has so much value.

One of the beliefs of pragmatism is that knowledge has

meaning only in its consequences. This suggests that information has value only

if it is acted upon. Information that is stored in secret has no consequences.

By contrast, information that informs action needs to be both known and acted

upon. The more people who have access to this information and can act on it,

the more value it has.

What was missing from Shockley’s approach to this brand

new technology was a management style that took advantage of an abundance of

information. He did not like to give up control or information but that was

exactly what this new computer chip he’d helped to invent was perfectly made

for. Largely because of this, it was not Shockley who would become a

billionaire from computer chips. Instead, it would be a few of his employees.

The Summer of Pocket Protectors

1968 was the kind of year that would have made even

today’s 24-7 news coverage seem insufficient. In January, the North Vietnamese

launched the Tet offensive, making it all the way to the U.S. Embassy in

Saigon; this might have been the first indication that those unbeatable Americans

could be beaten. Civil rights demonstrations that devolved into deadly riots

were the backdrop for Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act. Martin

Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy - iconic figures even in life - were

assassinated within months of each other. The musical Hair opened on Broadway

and Yale announced that it would begin to admit women. For the first time in history,

someone saw the earth from space: astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and

William Anders became the first humans to see the dark side of the moon and the

earth as a whole, an image that transcended differences of borders and even

continents. Any one of these stories could have been enough to change modern

society. Yet in the midst of all these incredible events, two entrepreneurs

quietly began a company that would transform technology and business, a company

that would do as much to define Silicon Valley as any other.

Gordon Moore (b. 1929) and Robert Noyce (1927-1990) founded

Intel in July 1968. Moore gave his name to “Moore’s Law,” a prediction that the

power of computer chips would double every eighteen months. Here was something

akin to the magic of compound interest applied to technology or, more

specifically, information processing.

Moore and Noyce had originally worked for Shockley, but

they left his laboratory because they did not like his tyrannical management.

They then went to work for Fairchild Semiconductor, but left again, because,

“Fairchild was steeped in an East Coast, old-fashioned, hierarchical business

structure,” Noyce said in a 1988 interview. "I never wanted to be a part

of a company like that."[3]

It is worth noting that Moore and Noyce did not leave

their former employers because of technology or funding issues. They left

because of differences in management philosophy.

Once when I was at Intel, one of the employees asked if I

wanted to see the CEO’s cubicle. Note that this was an invitation to see his

cubicle, not his office. We walked over to a wall that was - like every other

wall on the floor - about five feet high, and I was able to look over the wall

into an office area complete with pictures of CEO Craig Barrett with people

like President Clinton. In most companies, one can quickly discern the

hierarchy based on dynamics in a meeting. The level of deference and the ease

of winning arguments are pretty clear indicators of who is where in the

organizational chart. By contrast, I have never been inside a company where it

was more difficult to discern rank than Intel. Depending on the topic,

completely different people could be assertive or deferential. One of Intel’s

values is something like “constructive confrontation,” and this certainly

played out in more than one meeting I attended. When a company makes

investments in the billions, it cannot afford to make a mistake simply because

people have quaint notions about respect for authority. Intel’s culture seems

to do everything to drive facts and reasons ahead of position and formal

authority. This egalitarian style probably traces back to its founders rejection

of the management style of their former employer, Shockley.

Shockley Labs no longer exists. Intel has a market cap of

more than $150 billion.[4]

Intel’s net profit in the most recent year was over $11 billion, and it employs

more than 100,000 people worldwide. Moore and Noyce’s open culture made a

difference.

Information technology has little value in a culture that

hoards information. Information technology makes sense as a means to store,

distribute, and give access to information and has value as tool for problem

solving and decision-making.

The pioneers of information technology, like Moore and

Noyce, understood this and realized - at some level - that it made little or no

sense to create hierarchies where information was held and decisions were made

at one level and people were merely instructed at another. The knowledge worker

needed information technology as a basis for decisions and action. Before 1830,

up until the time of the railroad, the information sector of the American

workforce was less than 1 percent.[5]

By the close of the 20th century, nearly everyone seemed to need technology for

storing and processing information.

By paying double typical wages, Henry Ford created a new

generation of consumers for his car. Moore and Noyce did not just help to create

information technology; they helped to popularize a management culture that took

advantage of this amazing new technology.

[1]

Time, Jon Gertner, “How Bell Labs Invented the World We Live in Today,” March

21, 2012. http://business.time.com/2012/03/21/how-bell-labs-invented-the-world-we-live-in-today/

[3]

Daniel Gross, ed., Forbes: Greatest Business

Stories of All Time (New

York: John Wiley &

Sons, 1996), 251.

[4]

This taken from stock market quotes at end of 2014.

[5]

Beniger, The Control Revolution, 23.

Income Inequality and Living in the Top 1%

Whether it offends you or delights you, consider for a moment the political debate about the top 1%. They should be taxed more, the argument goes, and more of their income should go to those at the bottom. Let's say for a moment that you agree and that you think - for example - that the top 1% should pay another 5% of their income in taxes.

If you make $32,400 a year, you are in the top 1%. That's $16 an hour, working full-time. In some parts of the US, $15 will soon be the minimum wage. $16 an hour may not seem like a lot but it makes your income higher than 99% of the world's population. Do you feel an obligation to pay 5% more of your taxes to help those at the bottom? Would you send another $1,620 a year to help the world's poor?

Now you might argue that you have to live in a place where $32,400 barely covers your expenses. Housing alone would eat up a big chunk of your income, and this gets to one problem with examining high-income in the US. With median home prices of one million, the Bay Area (including Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo counties) is a place from which we get reports of homeless people making $80,000 a year. Palo Alto - home to Stanford's campus and neighbor to Google, Apple and Facebook campuses - is considering a proposal that would help to subsidize housing for households making only $150,000 to $250,000 a year.

The differences between what it costs to live in San Francisco (where median home prices are $1,129,800) and Gary Indiana (where median home prices are $47,500) are so great as to render national discussions about income disparity almost meaningless.

If you lived in rural Wyoming or Mississippi, $100,000 would feel very different than it would in Manhattan or Bethesda, MA. And most of the good jobs are being created in places where home prices are high. Whether you are an American making $32,400 or a New Yorker making $100,000, your income relative to people outside of your community (whether you define the community as the US or as New York) says little about your lifestyle. From afar you might appear rich but your reality might be barely getting by. Partly this is because so many of our expenses are set by market prices determined by the people around us. Partly it is because our expectations of normal are set by the folks around us.

And this is one fascinating thing about relative wealth and income. We rarely think of ourselves as rich when we're living among people with roughly the same income. And we do tend to live among people in our demographic group. I was chatting with someone who lived in a neighborhood with multi-million dollar homes and they were talking about how rich their neighbors were. Steve Jobs used to socialize with Larry Ellison - who has been on the top ten richest people list a number of years. Jobs' son called Ellison "our rich friend." Even the rich know someone they consider rich. Every group - even groups who are themselves in someone else's 1% - know someone in their 1% and to them, that guy is the rich one.

And later in the day after writing this, I find this article on how much $100 is worth in different states.

If you make $32,400 a year, you are in the top 1%. That's $16 an hour, working full-time. In some parts of the US, $15 will soon be the minimum wage. $16 an hour may not seem like a lot but it makes your income higher than 99% of the world's population. Do you feel an obligation to pay 5% more of your taxes to help those at the bottom? Would you send another $1,620 a year to help the world's poor?

Now you might argue that you have to live in a place where $32,400 barely covers your expenses. Housing alone would eat up a big chunk of your income, and this gets to one problem with examining high-income in the US. With median home prices of one million, the Bay Area (including Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo counties) is a place from which we get reports of homeless people making $80,000 a year. Palo Alto - home to Stanford's campus and neighbor to Google, Apple and Facebook campuses - is considering a proposal that would help to subsidize housing for households making only $150,000 to $250,000 a year.

The differences between what it costs to live in San Francisco (where median home prices are $1,129,800) and Gary Indiana (where median home prices are $47,500) are so great as to render national discussions about income disparity almost meaningless.

If you lived in rural Wyoming or Mississippi, $100,000 would feel very different than it would in Manhattan or Bethesda, MA. And most of the good jobs are being created in places where home prices are high. Whether you are an American making $32,400 or a New Yorker making $100,000, your income relative to people outside of your community (whether you define the community as the US or as New York) says little about your lifestyle. From afar you might appear rich but your reality might be barely getting by. Partly this is because so many of our expenses are set by market prices determined by the people around us. Partly it is because our expectations of normal are set by the folks around us.

And this is one fascinating thing about relative wealth and income. We rarely think of ourselves as rich when we're living among people with roughly the same income. And we do tend to live among people in our demographic group. I was chatting with someone who lived in a neighborhood with multi-million dollar homes and they were talking about how rich their neighbors were. Steve Jobs used to socialize with Larry Ellison - who has been on the top ten richest people list a number of years. Jobs' son called Ellison "our rich friend." Even the rich know someone they consider rich. Every group - even groups who are themselves in someone else's 1% - know someone in their 1% and to them, that guy is the rich one.

And later in the day after writing this, I find this article on how much $100 is worth in different states.

29 April 2016

M is for Mother - the letter that predated the alphabet by millennia

Mother's Day is in about a week. The "mmm" sound babies make so naturally lends itself to "ma," or "mom," one of their earliest sounds morphing into one of their earliest words.

I recently read Peter Watson's Great Divide, the story of how human cultures evolved separately in the Americas and Eurasia after the Bering Strait closed about 16,000 years ago, and came across this fascinating tidbit about the letter M.

I recently read Peter Watson's Great Divide, the story of how human cultures evolved separately in the Americas and Eurasia after the Bering Strait closed about 16,000 years ago, and came across this fascinating tidbit about the letter M.

“The ‘birth-giving Goddess,’ with parted legs and pubic triangle, became a form of shorthand, as the capital letter M as ‘the ideogram of the Great Goddess.’”

This thousands of years before linear writing. Kind of fascinating to think that the birth of the alphabet was itself a symbol for birth. That seems fitting.

Happy (almost) Mother's Day.

Happy (almost) Mother's Day.

24 April 2016

Bad Job Markets Kill People

Everyone knows that bad foreign policy kills. Failure to intervene can essentially sanction genocide and willingness to intervene can mean prolonging or exacerbating a civil war.

Domestic policy kills as well. Business cycles are inevitable but they can be made more severe or more prolonged by bad policy. And when unemployment goes up, so do suicide rates.

Suicide rates rose 24% from 1999 to 2014. The biggest jump was from 2006 to 2014, when so many lives were financially devastated.

Anyone puzzled over Sanders' or Trump's support fails to appreciate the emotional toll of the last decade. This is not something people recover from easily or quickly.

Last decade was devastating in terms of job growth.

Domestic policy kills as well. Business cycles are inevitable but they can be made more severe or more prolonged by bad policy. And when unemployment goes up, so do suicide rates.

Suicide rates rose 24% from 1999 to 2014. The biggest jump was from 2006 to 2014, when so many lives were financially devastated.

Anyone puzzled over Sanders' or Trump's support fails to appreciate the emotional toll of the last decade. This is not something people recover from easily or quickly.

Last decade was devastating in terms of job growth.

In the last three decades of the 20th century, the American economy created roughly 20 million jobs per decade, a rate equal to about 9% of the population. In the first decade of this century, the economy LOST 1.1 million jobs. And now in this second decade, it's on pace to create nearly 23 million jobs, but a number equal to only 7% of the population. We're on track for a good but not great decade. The rate of job creation is decent but the state of the job market is still impacted by this awful decade defined by a dot-com bust, a 9/11 recession, and the Great Recession. It looks like it will take at least a decade to recover from the last decade and of course even that glosses over hundreds of thousands of lives that will never fully recover from lost pensions, homes, and years of employment.

As mentioned, business cycles are inevitable. Still, policies can make the difference between long or short, deep or shallow recessions. And it's not just abstract numbers like unemployment that are impacted when we get these policies wrong. It's actual lives.

21 April 2016

Inventions Breed More Inventions - Just Another Reason for Optimism

Invention begets new invention. Patents are steadily going up and even the rate of patents seems to be steadily going up.

Here's a graph of data from the US Patent Office.

As you can see, patent numbers have almost shifted to a new plateau in this decade. Although it has dropped off a bit in the last couple of years, I don't think that it will level off.

When talking about something like economic progress and innovation, the comparison with last year is less important than the comparison with last decade. Within this data set, there are four years - 2012 through 2015 - that can be compared with the previous decade. That is impressive for two reasons. One, this decade is significantly higher than last. Two, the rate at which it is getting higher is getting higher.

In 2012, there were 39% more patents than in 2002. In 2013, there were 52% more than in 2003. In 2014, there were 72% more patents than there were in 2004. And last year, there were nearly 90% more (almost double) the number of patents that there were in 2005.

Here's a graph of data from the US Patent Office.

As you can see, patent numbers have almost shifted to a new plateau in this decade. Although it has dropped off a bit in the last couple of years, I don't think that it will level off.

When talking about something like economic progress and innovation, the comparison with last year is less important than the comparison with last decade. Within this data set, there are four years - 2012 through 2015 - that can be compared with the previous decade. That is impressive for two reasons. One, this decade is significantly higher than last. Two, the rate at which it is getting higher is getting higher.

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

| 39.2% | 52.0% | 71.6% | 88.9% |

In 2012, there were 39% more patents than in 2002. In 2013, there were 52% more than in 2003. In 2014, there were 72% more patents than there were in 2004. And last year, there were nearly 90% more (almost double) the number of patents that there were in 2005.

One reason I think that this rate of innovation will continue to accelerate is that innovation is a function of interaction. You see a carriage behind a horse and you see a combustion engine with a certain amount of horse power and you get the idea to combine the carriage and the engine into a horseless carriage. You see a mouth piece and a telegraph cable and you get an idea of sending voices down wires, turning the telegraph infrastructure into a telephone system.

As we innovate more, there is a bigger foundation for further innovation. Benjamin Franklin once said, "Money makes money and the money money makes makes money too." This remains one of the more whimsically accurate descriptions of compound interest. Your $100 makes $5 by year end. Next year, that $5 also makes money. The money your money makes also makes money.

Innovations work in a similar way. Once you invent a carriage and invent an engine, you have the possibility of innovations that combine those. Once you invent a car and a smart phone, innovations like Uber are possible. And as the number of inventions in the world go up, the number of inventions that can be added to the world goes up. The rate at which inventions are getting higher will get higher as there are more inventions in the world.

And as impressive as US growth is, the rate of growth in foreign patents is even better. This exchange of ideas and innovations across the planet is becoming even more pronounced.

Here you can see that foreign patents in 2015 are more than double what they were in 2005.

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

| 64.4% | 77.8% | 95.0% | 127.6% |

As the developed world comes online and education levels rise, there is plenty of reason to think that this rate of innovation will continue to rise. The first car might have been invented in one place but cars are now everywhere. Good innovations spread, which means that as more parts of the world are innovating, more cool products will be everywhere. If you want a reason for optimism, this is as solid as any.

06 April 2016

Endorsing Hillary Clinton

In spite of all the criticism it has received, it is possible that the Republican Party is getting better aligned with the American people. Both the American people and the GOP establishment now agree that the GOP presidential candidates are awful.

Oddly, Trump's behavior has been so atrocious that it has distracted from what is most notable about this campaign: there are stark differences between the remaining candidates. Clinton very much represents a continuation of the status quo (her policies are the most like Obama's of any candidate), Sanders represent a serious move to the left, Cruz an even more serious move to the right, and Trump a serious leap into fantasy.

Cruz wants to get rid of the Environmental Protection Agency, for example. And the Education Department, the IRS, the Department of Commerce, and HUD - housing and urban development. In addition, he would eliminate another 25 agencies such as the corporation for public broadcasting, national endowment for the arts, and any agency attempting to regulate greenhouse gases or climate change. (If there were a Galileo of climate change, Cruz would put him under house arrest.) And then he would cut government spending another trillion dollars a year. His policies represent an unwinding of a century of change and a return to 1916 policies. Or perhaps 1816.

One simple way to think about Sanders proposals is that he simply wants to make our policies more like Europe's. A client I was talking with from Italy said that Sanders policies, while considered so liberal here, are what European candidates on even the furthest right agree on: universal healthcare, for instance, is not even questioned in Europe. I think that by the time millennials are my age - that is, in roughly a generation - most of what Bernie is proposing will be normal. About a century ago this country made a push to finance public education for K-12. It seems reasonable that university education has become as essential to a career now as high school education had become then and should be funded similarly. Bernie has a protectionist edge, though, that could reverse economic progress in poorer regions of the world. He has mentioned that fair trade probably means avoiding trade with countries where prevailing wages are lower than the US. The percentage of the global population living in absolute poverty (defined as $1 a day) has dropped by roughly 90% since the 1980s. This is a wonderful thing and refusal of the world's biggest economy to trade with any region poorer than ours could be a serious setback to this. Bernie's economic and military isolationism would better match a country the size of, say, Vermont, than the world's biggest economy. Eugene Debs ran as a socialist three or four times roughly a century ago. By one count he was wildly unsuccessful: he never came close to winning the presidency. By another count, he was wildly successful: so many of his policy proposals - like social security and women voting - were adopted. I think that Sanders will have a similar influence over future policies. GOP supporters are very old and Sanders supporters are very young. Many of his policy proposals do seem inevitable. But for now, the fact that Sanders tax plan would raise taxes on median household income by a startling amount (as in, I'm sure the average household would be startled by the fact that their taxes would go up by roughly $500 a month) is enough to doom his campaign.

And Trump's policies are simply incoherent. I've wondered if he's stupid or just hopes that 51% of the American people are but it seems increasingly clear that his mind is a dangerous waste. Unlike Cruz, Clinton, or Sanders, he hasn't really put forward any coherent policies that could be seriously analyzed. For this reason alone, he ought not to be seriously considered.

Hillary Clinton is easily the most sophisticated thinker in the bunch. She's the only candidate who seems able to include "if, then" considerations that include everything from nuanced policy considerations to the personalities of various world leaders. Her model of reality is as complex and rich with nuance as Cruz's model is simplistic and barren of details. Putting aside the fact that she's a centrist similar in many ways to her husband and Obama, one simple fact that is too rarely mentioned is that none of the candidates could begin to compare with her on an understanding of the latest research and policy options on issues as varied as climate change, child development, poverty, terrorism, Russia's geopolitics or China's economy.

For a host of reasons I support Hillary Clinton. I know the sophisticated thing to say is that I do so with reluctance but I do so happily. I think that, like Obama, Hillary is a wonderfully qualified and good person who we are lucky to have competing for our top office. Within the S and P 500, average CEO pay was $13.8 million in 2014. We pay our presidents $400,000. About what a high-level corporate director can make. We are lucky to get someone of her caliber. Her model of the world is at least twice as sophisticated as that of her opponents. (It's worth remembering that the original IQ tests were developed to cut the population in half at 100. For every person with an IQ of 130, there is one with an IQ of 70. Half of all people are below average. Her intelligence is a definite plus for policy. It's not obviously a plus for politics. I suspect that quite a few people hear "blah, blah, blah" when she talks about the middle east or income inequality.) Even if Hillary were only as good as the 17 men she has run against in this election, though, I would vote for her. Why? Even if all else were equal, it is time for a woman president. And of course Hillary Clinton is more than their equal.

Maybe the next time we elect a woman it could be someone just as smart - rather than twice as smart - as the men she is running against. It would be nice for girls growing up to think that they don't have to be twice as good to compete.

Finally, the big reason to do something dramatic - like vote for candidates who represent a huge departure from the status quo - is because things are terrible. After a record 66 months of uninterrupted job creation that has halved the unemployment rate and a tripling of the S and P 500 since March of Obama's first year, it's hard to make the argument that we're on the wrong path. Wages are rising now, as happens once the labor market tightens. We're on the right track even though we had to dig ourselves out of a huge hole left by the Great Recession. After the great economy we'd enjoyed under Bill Clinton, voters thought it was time for a real change in direction. Maybe this time it's worth staying with the policies that made things better, not worse. Progress moves more slowly than disaster but it's got a happier destination.

Oddly, Trump's behavior has been so atrocious that it has distracted from what is most notable about this campaign: there are stark differences between the remaining candidates. Clinton very much represents a continuation of the status quo (her policies are the most like Obama's of any candidate), Sanders represent a serious move to the left, Cruz an even more serious move to the right, and Trump a serious leap into fantasy.

Cruz wants to get rid of the Environmental Protection Agency, for example. And the Education Department, the IRS, the Department of Commerce, and HUD - housing and urban development. In addition, he would eliminate another 25 agencies such as the corporation for public broadcasting, national endowment for the arts, and any agency attempting to regulate greenhouse gases or climate change. (If there were a Galileo of climate change, Cruz would put him under house arrest.) And then he would cut government spending another trillion dollars a year. His policies represent an unwinding of a century of change and a return to 1916 policies. Or perhaps 1816.

One simple way to think about Sanders proposals is that he simply wants to make our policies more like Europe's. A client I was talking with from Italy said that Sanders policies, while considered so liberal here, are what European candidates on even the furthest right agree on: universal healthcare, for instance, is not even questioned in Europe. I think that by the time millennials are my age - that is, in roughly a generation - most of what Bernie is proposing will be normal. About a century ago this country made a push to finance public education for K-12. It seems reasonable that university education has become as essential to a career now as high school education had become then and should be funded similarly. Bernie has a protectionist edge, though, that could reverse economic progress in poorer regions of the world. He has mentioned that fair trade probably means avoiding trade with countries where prevailing wages are lower than the US. The percentage of the global population living in absolute poverty (defined as $1 a day) has dropped by roughly 90% since the 1980s. This is a wonderful thing and refusal of the world's biggest economy to trade with any region poorer than ours could be a serious setback to this. Bernie's economic and military isolationism would better match a country the size of, say, Vermont, than the world's biggest economy. Eugene Debs ran as a socialist three or four times roughly a century ago. By one count he was wildly unsuccessful: he never came close to winning the presidency. By another count, he was wildly successful: so many of his policy proposals - like social security and women voting - were adopted. I think that Sanders will have a similar influence over future policies. GOP supporters are very old and Sanders supporters are very young. Many of his policy proposals do seem inevitable. But for now, the fact that Sanders tax plan would raise taxes on median household income by a startling amount (as in, I'm sure the average household would be startled by the fact that their taxes would go up by roughly $500 a month) is enough to doom his campaign.

And Trump's policies are simply incoherent. I've wondered if he's stupid or just hopes that 51% of the American people are but it seems increasingly clear that his mind is a dangerous waste. Unlike Cruz, Clinton, or Sanders, he hasn't really put forward any coherent policies that could be seriously analyzed. For this reason alone, he ought not to be seriously considered.

Hillary Clinton is easily the most sophisticated thinker in the bunch. She's the only candidate who seems able to include "if, then" considerations that include everything from nuanced policy considerations to the personalities of various world leaders. Her model of reality is as complex and rich with nuance as Cruz's model is simplistic and barren of details. Putting aside the fact that she's a centrist similar in many ways to her husband and Obama, one simple fact that is too rarely mentioned is that none of the candidates could begin to compare with her on an understanding of the latest research and policy options on issues as varied as climate change, child development, poverty, terrorism, Russia's geopolitics or China's economy.

For a host of reasons I support Hillary Clinton. I know the sophisticated thing to say is that I do so with reluctance but I do so happily. I think that, like Obama, Hillary is a wonderfully qualified and good person who we are lucky to have competing for our top office. Within the S and P 500, average CEO pay was $13.8 million in 2014. We pay our presidents $400,000. About what a high-level corporate director can make. We are lucky to get someone of her caliber. Her model of the world is at least twice as sophisticated as that of her opponents. (It's worth remembering that the original IQ tests were developed to cut the population in half at 100. For every person with an IQ of 130, there is one with an IQ of 70. Half of all people are below average. Her intelligence is a definite plus for policy. It's not obviously a plus for politics. I suspect that quite a few people hear "blah, blah, blah" when she talks about the middle east or income inequality.) Even if Hillary were only as good as the 17 men she has run against in this election, though, I would vote for her. Why? Even if all else were equal, it is time for a woman president. And of course Hillary Clinton is more than their equal.

|

| What if she lived in a world where a girl could grow up to become president? Who knew that about the 1950s? |

Finally, the big reason to do something dramatic - like vote for candidates who represent a huge departure from the status quo - is because things are terrible. After a record 66 months of uninterrupted job creation that has halved the unemployment rate and a tripling of the S and P 500 since March of Obama's first year, it's hard to make the argument that we're on the wrong path. Wages are rising now, as happens once the labor market tightens. We're on the right track even though we had to dig ourselves out of a huge hole left by the Great Recession. After the great economy we'd enjoyed under Bill Clinton, voters thought it was time for a real change in direction. Maybe this time it's worth staying with the policies that made things better, not worse. Progress moves more slowly than disaster but it's got a happier destination.

03 April 2016

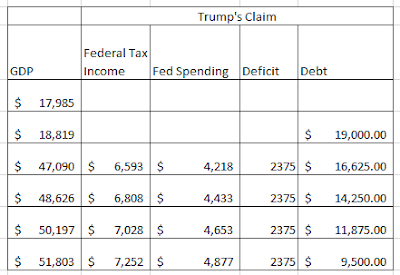

Donald Trump's Delusional Economics (Warning - This Post Contains Highly Technical Math: Arithmetic)

Yesterday Trump had an interview with Bob Woodward of Watergate fame. I used to wonder whether Trump was an idiot or just hoped that 51% of voters were. This interview made it clear that Trump's chief obstacle to understanding the economy is a tenuous grasp of arithmetic.

Donald plans to cut the top tax rate on individuals from nearly 40% to 25% and to cut corporate income tax from 35% to 15%. Credible analysis of his plans suggest that it would cut federal revenues by about $1 trillion per year, reducing federal taxes as a percentage of GDP from 19% to 14%.

Donald has revealed no plans to cut government spending, so the best estimate is that his plan will increase the annual deficit about $1 trillion per year. Without offsetting cuts, every dollar of lost tax revenue is one more dollar of new debt.

In yesterday's interview, Donald claimed that he would eliminate the $19 trillion government debt within 8 years.

Let's take him at his word for a moment and assume that because he's president the economy will magically grow enough to offset not just the $1 trillion in lost taxes but pay down another $2.375 trillion of debt each year. (That's what it takes to reduce a $19 trillion debt to zero in 8 years.)

Here are the numbers:

Donald drops federal taxes from average of 19% of GDP to 14%.

Donald keeps government spending stable.

Donald reduces the national debt by $19 trillion in 8 years.

The current projections look like this:

Donald plans to cut the top tax rate on individuals from nearly 40% to 25% and to cut corporate income tax from 35% to 15%. Credible analysis of his plans suggest that it would cut federal revenues by about $1 trillion per year, reducing federal taxes as a percentage of GDP from 19% to 14%.

Donald has revealed no plans to cut government spending, so the best estimate is that his plan will increase the annual deficit about $1 trillion per year. Without offsetting cuts, every dollar of lost tax revenue is one more dollar of new debt.

In yesterday's interview, Donald claimed that he would eliminate the $19 trillion government debt within 8 years.

Let's take him at his word for a moment and assume that because he's president the economy will magically grow enough to offset not just the $1 trillion in lost taxes but pay down another $2.375 trillion of debt each year. (That's what it takes to reduce a $19 trillion debt to zero in 8 years.)

Here are the numbers:

Donald drops federal taxes from average of 19% of GDP to 14%.

Donald keeps government spending stable.

Donald reduces the national debt by $19 trillion in 8 years.

The current projections look like this:

What is Trump promising? What sort of GDP would allow him to cut taxes as a percentage of GDP AND reduce the debt? This:

To make his promises add up would mean GDP leaping from close to $20 trillion to roughly $50 trillion, which is about what total global GDP is right now.

Where does Donald get his information? It's hard to tell if it is from Marvel or DC but it's certainly a comic book and not a text book.

02 April 2016

Why Profits Are Not Too High and Are Not Done Rising

Even the Economist has joined the chorus claiming that corporate "Profits are too high." It's time to challenge a popular delusion about profits so that my seven readers can know what the Economist's seven million readers apparently don't.

Profits should get progressively higher with economic progress. Why? Profits allow you to make money without having to commit your time to the enterprise. (Doing time is something employees and prisoners do.) The problem is not that profits are too high. The problem is that they are not yet high enough and are not shared widely enough. To make profits even higher and share them more broadly will be one of the outcomes of the popularization of entrepreneurship. But first, just a simple reminder of what profits are.

Andy Warhol went to the store and bought cans of Campbell’s soup, paying pennies per can. He also went to the artist supply store and bought canvases and paints and paint brushes, paying dollars for these inputs. He turned these cans of soup into a series of 32 small paintings he then sold for $1,000. That was a good return for grocery shopping in 1964. Were his profits too high? Should he have paid more for the soup or sold his paintings for less? The market didn’t think so. The art dealer who bought the 32 canvases eventually sold them for $15 million. In any case, he wasn't paid some reasonable markup for his soup can costs. He was paid for the value he created.

Andy Warhol went to the store and bought cans of Campbell’s soup, paying pennies per can. He also went to the artist supply store and bought canvases and paints and paint brushes, paying dollars for these inputs. He turned these cans of soup into a series of 32 small paintings he then sold for $1,000. That was a good return for grocery shopping in 1964. Were his profits too high? Should he have paid more for the soup or sold his paintings for less? The market didn’t think so. The art dealer who bought the 32 canvases eventually sold them for $15 million. In any case, he wasn't paid some reasonable markup for his soup can costs. He was paid for the value he created.

Imagine that you have designed a box with four of your friends and you agree to share ownership of the box equally. You agree to all make salaries of, say, $30,000 a year. Given your education and experience, you could get jobs making 3 to 6X that much in the roles of software programmers or marketing guys or whatever but for now you are going to live on this $30,000 while you build a great box. You don't need to hire anyone else. It's just you five doing this.

Now, imagine that you are successful. You've created a box that regularly turns $100 into $400.

Because it's such a great money maker, you can sell it for $105 million.

So, the employees in this startup of yours made just a fraction of what it could have in other companies but the entrepreneurs in your startup walked away with $21 million each for three years of work. You and your partners were paid only $90,000 in wages over 3 years but you "made" an average of $7,030,000 a year. (At this point it's worth pointing out that Steve Jobs worked as CEO for a dollar a year. And billions in equity. He liked to quip that he got 50 cents a year just for showing up and the other 50 cents was for actual work. The idea that the employee part of you would be paid a small amount and the entrepreneur part of you would be paid more is not novel. It already happens.)

In this example you feel no outrage because employees and entrepreneurs are the same people. And in this scenario you would likely agree that it makes sense to make the box as efficient at generating profit as possible. It makes no more sense to regulate these boxes to be inefficient at generating profit than it does to regulate cars to get low gas mileage. So back to the problems.

First of all, we still have a dated notion of investment. Once upon a time, investment referred to the money needed to buy capital that would produce goods. Labor would work with the capital (the classic example being a factory that hired workers to work on its assembly lines) and it would get its wage while the capitalists who put up the money would get their profits. It is this old model that The Economist is referring to when it says that too much profit is a bad thing. In this model, whatever capitalists get, labor doesn’t.

But business is more complex than that now. There are so many things dated about this model, but I’ll just focus on one of them for now: intellectual capital is now the real investment. It’s intellectual capital that will be the biggest driver of profits (even if it is not currently getting the biggest returns.)

What’s obvious with programmers or designers is also true even of fast-food and factory workers. To stay competitive, such jobs have to be infused with steady improvements and occasional breakthroughs in process and product. This doesn't just come from headquarters. In fact, properly done it's more likely to come from the minds of the of the folks who are hands on with the product or service. (From variants on the sort of quality improvement initiatives that W. Edwards Deming advocated.) This, too, is a form of investment and deserves recognition. Someone who is steadily improving the process for building kitchen counters or making tastier sandwiches is also creating value through experimentation, discovery, and knowledge. A person making pickles could be adding more value through creativity than a person making posters.

Profits will increase as we popularize entrepreneurship, making more employees more entrepreneurial. One of the ways the popularization of entrepreneurship would show up is through employees taking ownership of process and product evolution and – as befits ownership – gaining a return for such work. If higher productivity roughly tracks with higher wages, higher creativity should track with higher equity shares.

Business is a black box that brings money in one end and spits money out the other end. We are getting better at designing and redesigning businesses to create larger gaps between the costs of inputs and the value of outputs. The problem isn’t that profits are going up. The problem is that we have a model that inaccurately assumes that the investment easiest to measure is the investment that is doing the most to create these profits. It's not just the $100 an investor puts into the firm that deserves a return; it's also the knowledge that an employee brings in and even more importantly, the creativity they apply. A more realistic assessment of the source of profits would mean a more equitable spread of the profits. Wages will drop as a percentage of total revenues but more equity will be created and more broadly spread.

Profits should get progressively higher with economic progress. Why? Profits allow you to make money without having to commit your time to the enterprise. (Doing time is something employees and prisoners do.) The problem is not that profits are too high. The problem is that they are not yet high enough and are not shared widely enough. To make profits even higher and share them more broadly will be one of the outcomes of the popularization of entrepreneurship. But first, just a simple reminder of what profits are.

When you start a business, it’s like trying to create a box that brings money in one end (those are your costs) and generates money out the other end (those are your revenues). If your revenues are more than your cost, you have a profit. If your revenues are less than your cost, you have a loss. It’s kind of odd to say that American businesses getting better at designing boxes to create profits is a bad thing.

Such a claim comes from the belief that profits are a return to capital. They are not. Profits are a return to creativity and entrepreneurship. You could borrow capital and pay it back interest. That's separate from profits you may or may not generate.

Such a claim comes from the belief that profits are a return to capital. They are not. Profits are a return to creativity and entrepreneurship. You could borrow capital and pay it back interest. That's separate from profits you may or may not generate.

Andy Warhol went to the store and bought cans of Campbell’s soup, paying pennies per can. He also went to the artist supply store and bought canvases and paints and paint brushes, paying dollars for these inputs. He turned these cans of soup into a series of 32 small paintings he then sold for $1,000. That was a good return for grocery shopping in 1964. Were his profits too high? Should he have paid more for the soup or sold his paintings for less? The market didn’t think so. The art dealer who bought the 32 canvases eventually sold them for $15 million. In any case, he wasn't paid some reasonable markup for his soup can costs. He was paid for the value he created.

Andy Warhol went to the store and bought cans of Campbell’s soup, paying pennies per can. He also went to the artist supply store and bought canvases and paints and paint brushes, paying dollars for these inputs. He turned these cans of soup into a series of 32 small paintings he then sold for $1,000. That was a good return for grocery shopping in 1964. Were his profits too high? Should he have paid more for the soup or sold his paintings for less? The market didn’t think so. The art dealer who bought the 32 canvases eventually sold them for $15 million. In any case, he wasn't paid some reasonable markup for his soup can costs. He was paid for the value he created.

Input costs should be incidental to the value of what you generate. If you can create a million dollars of value from 39 cents worth of soup and $4 worth of art supplies, hallelujah to ya. Profits are a reward for creativity.

So what is the real problem?

The real problem is that we don’t create enough profits and don’t spread them around more evenly. Those two problems are related. First a quick digression on companies.

Imagine that you have designed a box with four of your friends and you agree to share ownership of the box equally. You agree to all make salaries of, say, $30,000 a year. Given your education and experience, you could get jobs making 3 to 6X that much in the roles of software programmers or marketing guys or whatever but for now you are going to live on this $30,000 while you build a great box. You don't need to hire anyone else. It's just you five doing this.

Now, imagine that you are successful. You've created a box that regularly turns $100 into $400.

Because it's such a great money maker, you can sell it for $105 million.

So, the employees in this startup of yours made just a fraction of what it could have in other companies but the entrepreneurs in your startup walked away with $21 million each for three years of work. You and your partners were paid only $90,000 in wages over 3 years but you "made" an average of $7,030,000 a year. (At this point it's worth pointing out that Steve Jobs worked as CEO for a dollar a year. And billions in equity. He liked to quip that he got 50 cents a year just for showing up and the other 50 cents was for actual work. The idea that the employee part of you would be paid a small amount and the entrepreneur part of you would be paid more is not novel. It already happens.)

In this example you feel no outrage because employees and entrepreneurs are the same people. And in this scenario you would likely agree that it makes sense to make the box as efficient at generating profit as possible. It makes no more sense to regulate these boxes to be inefficient at generating profit than it does to regulate cars to get low gas mileage. So back to the problems.

First of all, we still have a dated notion of investment. Once upon a time, investment referred to the money needed to buy capital that would produce goods. Labor would work with the capital (the classic example being a factory that hired workers to work on its assembly lines) and it would get its wage while the capitalists who put up the money would get their profits. It is this old model that The Economist is referring to when it says that too much profit is a bad thing. In this model, whatever capitalists get, labor doesn’t.

But business is more complex than that now. There are so many things dated about this model, but I’ll just focus on one of them for now: intellectual capital is now the real investment. It’s intellectual capital that will be the biggest driver of profits (even if it is not currently getting the biggest returns.)

A software programmer can create code on a laptop that he owned even before joining a company. To pretend that the revenue from the code he writes should mostly go the “capitalist” who bought his new, $1,000 laptop is silly. The real capital is his knowledge of coding. In this model of the world, it only makes sense that the programmer be treated partly like an employee (that's how he earns his wage for work) and partly like a capitalist (that should show up as a return on his investment for knowledge). That is, the model for the modern work has to include treating knowledge work as an investment.

What’s obvious with programmers or designers is also true even of fast-food and factory workers. To stay competitive, such jobs have to be infused with steady improvements and occasional breakthroughs in process and product. This doesn't just come from headquarters. In fact, properly done it's more likely to come from the minds of the of the folks who are hands on with the product or service. (From variants on the sort of quality improvement initiatives that W. Edwards Deming advocated.) This, too, is a form of investment and deserves recognition. Someone who is steadily improving the process for building kitchen counters or making tastier sandwiches is also creating value through experimentation, discovery, and knowledge. A person making pickles could be adding more value through creativity than a person making posters.

Profits will increase as we popularize entrepreneurship, making more employees more entrepreneurial. One of the ways the popularization of entrepreneurship would show up is through employees taking ownership of process and product evolution and – as befits ownership – gaining a return for such work. If higher productivity roughly tracks with higher wages, higher creativity should track with higher equity shares.

Business is a black box that brings money in one end and spits money out the other end. We are getting better at designing and redesigning businesses to create larger gaps between the costs of inputs and the value of outputs. The problem isn’t that profits are going up. The problem is that we have a model that inaccurately assumes that the investment easiest to measure is the investment that is doing the most to create these profits. It's not just the $100 an investor puts into the firm that deserves a return; it's also the knowledge that an employee brings in and even more importantly, the creativity they apply. A more realistic assessment of the source of profits would mean a more equitable spread of the profits. Wages will drop as a percentage of total revenues but more equity will be created and more broadly spread.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)