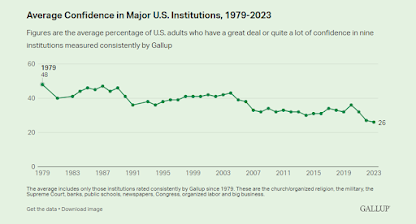

Gallup tracks the nation’s trust in some of America’s most defining institutions - churches, banks, the Supreme Court, the military, public schools, newspapers, Congress, organized labor, and big business. To varying degrees, Americans have lost confidence in all of them. In 1979, nearly half of the population had a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in these institutions. Now just 26% do.

We are in the middle of a very weird and long recession, one that has left many Americans anxious, angry, and convinced that conditions are bad and getting worse.

We are not in an economic recession. Labor and capital markets are thriving. Last month continued the longest streak of unemployment under 4% in half a century. The NASDAQ is up 12% so far this year – up 35% from a year ago. Inflation at 3.4% is still higher than its 21st century average of 2.6% but it continues to fall. In most periods of American history these numbers would be feeding talk about an economic boom.

We are in an institutional recession. That’s scarier. Why? We know how to deal with an economic recession but haven’t even begun the discussion about how to confront an institutional recession. Save for the dwindling handful of nerds who stand up to argue for the importance of church, universities, big-tech, or government bureaucracies, you’re more likely to hear loud criticism of institutions than any defense of them.

And that’s dangerous because our quality of life depends on institutions. We depend on thousands – millions - of people we don’t even know to grow, ship, and prepare our food, to make our clothes, to update our apps, and operate the seemingly invisible systems with thousands of parts that regulate our supply of goods, water, electricity, and information. And through "tasks" like work, worship, and learning, these institutions even create meaning.

These strangers create value for us through a vast web of institutions: schools that educate workers, law enforcement and courts that regulate, and corporations that make, ship, and deliver goods and services. Our small network of family and friends would collapse under the weight of the complexity our quality of life depends on. The decline in quality of life from where we are now to what we could sustain with the small groups our tribal impulses draw us toward would be precipitous. While we can afford to be unhappy with the myriad institutions that define our lives, we cannot afford to discard them or follow our worst impulses into a world of Hatfield and McCoy-style alliances. Our modern world depends on millions of strangers working through and within hundreds of thousands of institutions. We need them to function.

It is difficult to understand Trump's allure without recognizing the deep disenchantment Americans feel toward their institutions. When people anywhere grow frustrated with their institutions, they often turn to strong men who promise to blowup or marginalize institutions.

There is a big problem with this. Strong men never deliver. The modern world is simply too complex to be run by dictate.

It's true that Putin literally kills political opponents. More prosaically, 20% of Russians do not have indoor plumbing. While the US has never defaulted on its bonds, Russia has al always defaulted on its 30-year bonds. Putin doesn’t deliver.

North and South Korea have been divided by a border since 1948. The stark contrast between the two countries cannot be attributed to differences in race, deep history, or language. One nation has been ruled by dictators, while the other has been led by democratic leaders who have generally respected South Korea’s institutions. The difference between strong men and strong institutions is striking. A South Korean generates as much GDP in seven days as a North Korean does in an entire year. South Korea’s per capita GDP exceeds $33,000, compared to just $900 per year in North Korea. Strong men capture attention and create great lives for themselves but deliver dismal results for their people.

We are living through a dramatic institutional recession that has been largely ignored and yet explains so much about America’s current mood and politics. The first step to addressing it is to appreciate how vital institutions are, how much they define us. The second step is to begin a conversation about how to redefine the institutions that define us. These steps could mark the beginning of the end of our institutional recession.

We are not in an economic recession. Labor and capital markets are thriving. Last month continued the longest streak of unemployment under 4% in half a century. The NASDAQ is up 12% so far this year – up 35% from a year ago. Inflation at 3.4% is still higher than its 21st century average of 2.6% but it continues to fall. In most periods of American history these numbers would be feeding talk about an economic boom.

We are in an institutional recession. That’s scarier. Why? We know how to deal with an economic recession but haven’t even begun the discussion about how to confront an institutional recession. Save for the dwindling handful of nerds who stand up to argue for the importance of church, universities, big-tech, or government bureaucracies, you’re more likely to hear loud criticism of institutions than any defense of them.

And that’s dangerous because our quality of life depends on institutions. We depend on thousands – millions - of people we don’t even know to grow, ship, and prepare our food, to make our clothes, to update our apps, and operate the seemingly invisible systems with thousands of parts that regulate our supply of goods, water, electricity, and information. And through "tasks" like work, worship, and learning, these institutions even create meaning.

These strangers create value for us through a vast web of institutions: schools that educate workers, law enforcement and courts that regulate, and corporations that make, ship, and deliver goods and services. Our small network of family and friends would collapse under the weight of the complexity our quality of life depends on. The decline in quality of life from where we are now to what we could sustain with the small groups our tribal impulses draw us toward would be precipitous. While we can afford to be unhappy with the myriad institutions that define our lives, we cannot afford to discard them or follow our worst impulses into a world of Hatfield and McCoy-style alliances. Our modern world depends on millions of strangers working through and within hundreds of thousands of institutions. We need them to function.

It is difficult to understand Trump's allure without recognizing the deep disenchantment Americans feel toward their institutions. When people anywhere grow frustrated with their institutions, they often turn to strong men who promise to blowup or marginalize institutions.

There is a big problem with this. Strong men never deliver. The modern world is simply too complex to be run by dictate.

It's true that Putin literally kills political opponents. More prosaically, 20% of Russians do not have indoor plumbing. While the US has never defaulted on its bonds, Russia has al always defaulted on its 30-year bonds. Putin doesn’t deliver.

North and South Korea have been divided by a border since 1948. The stark contrast between the two countries cannot be attributed to differences in race, deep history, or language. One nation has been ruled by dictators, while the other has been led by democratic leaders who have generally respected South Korea’s institutions. The difference between strong men and strong institutions is striking. A South Korean generates as much GDP in seven days as a North Korean does in an entire year. South Korea’s per capita GDP exceeds $33,000, compared to just $900 per year in North Korea. Strong men capture attention and create great lives for themselves but deliver dismal results for their people.

We are living through a dramatic institutional recession that has been largely ignored and yet explains so much about America’s current mood and politics. The first step to addressing it is to appreciate how vital institutions are, how much they define us. The second step is to begin a conversation about how to redefine the institutions that define us. These steps could mark the beginning of the end of our institutional recession.